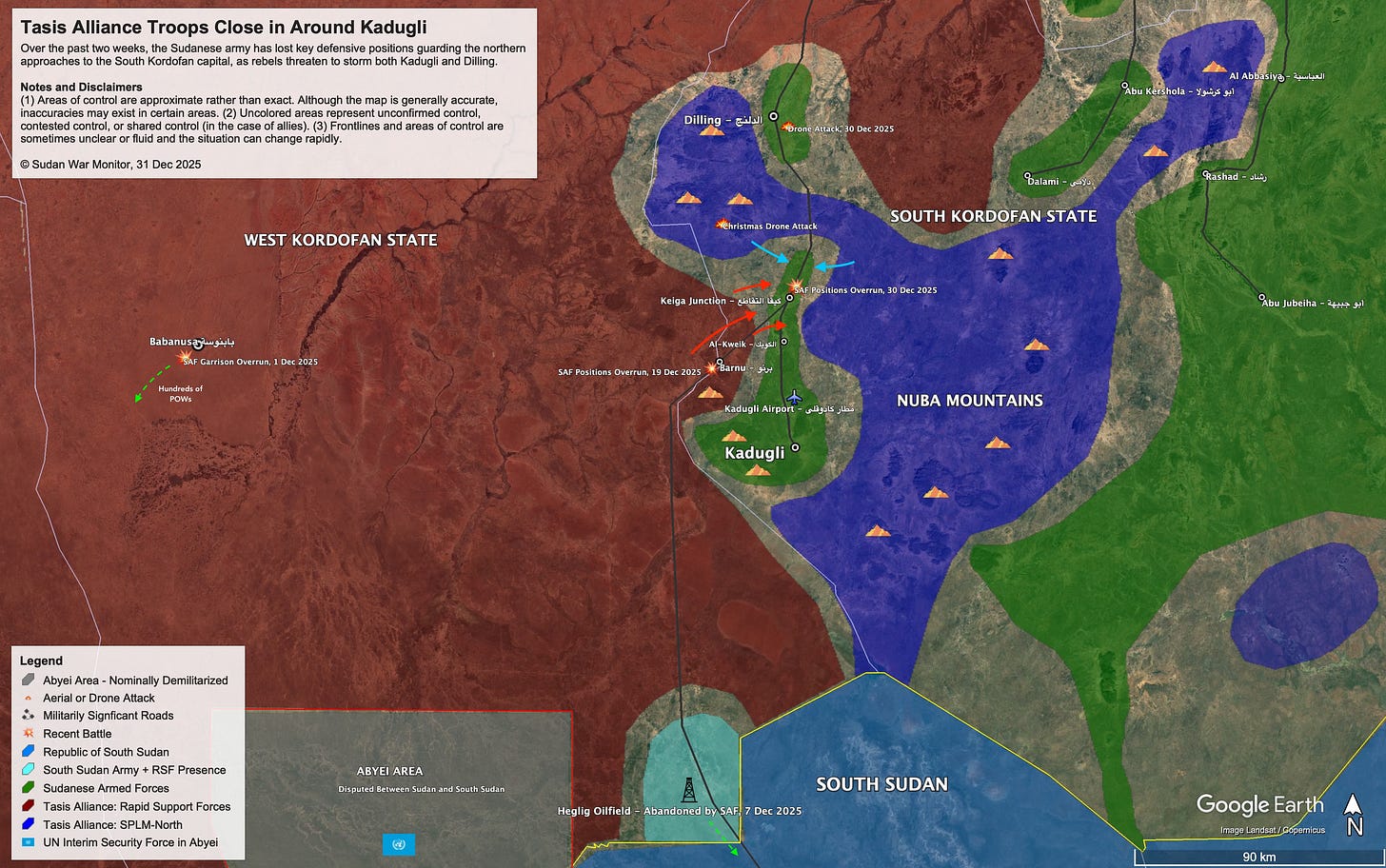

Allied Rebels Overrun Sudan Army Defenses Near South Kordofan Capital

Civilian Exodus from Besieged Cities of Kadugli and Dilling

Sudanese army defenses continue to break down around the cities of Kadugli and Dilling in South Kordofan, coinciding with an exodus of civilians amid famine and fears of imminent rebel attacks.

Army units in the area are outnumbered and facing shortages of critical supplies. Some soldiers are defecting or abandoning their positions. At present, there appears to be no ongoing army operation to relieve the imperiled cities. Past efforts to reinforce and resupply Dilling and Kadugli, launched from SAF-held territory in North Kordofan, were repulsed.

The Rapid Support Forces (RSF) have dispatched their prominent field commander, Colonel Saleh Al-Futi, who oversaw the successful assaults on the army’s 22nd Division (Babanusa) and 16th Division (Nyala), to lead operations in the Kadugli theater.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Sudan War Monitor to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.