Battle for Khartoum continues to draw fighters from across the Sahel

Recent arrivals from Chad and Um Dukhun

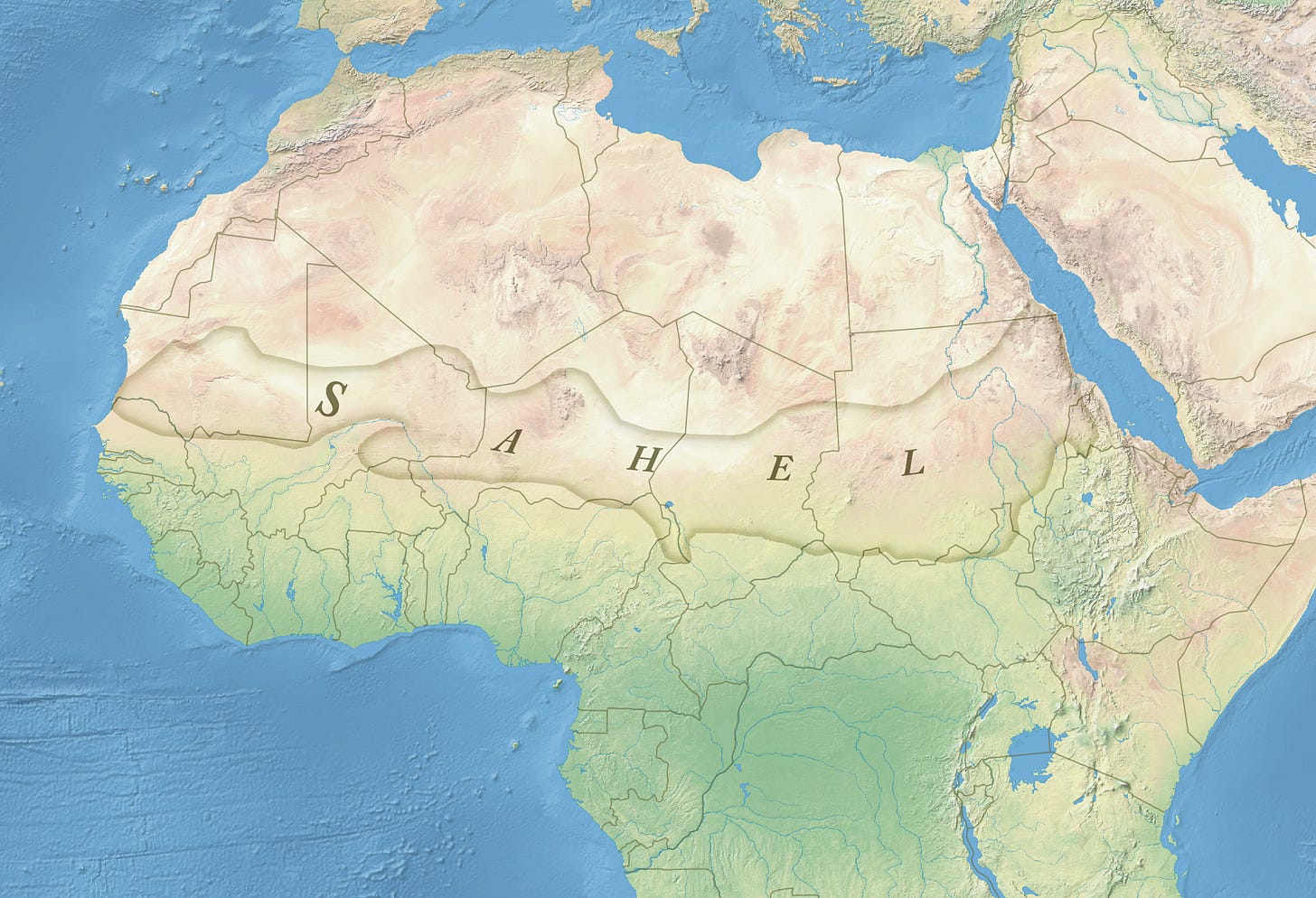

New groups of fighters from Darfur, Chad, the Central African Republic, and Libya continue arriving in central Sudan to join the ranks of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which are fighting for power in the capital.

The RSF now control a territory larger than most European countries, approximately the size of Germany—not counting vast northern desert regions through which they are able to move freely. Their ‘control’ over this territory, however, is marked by lawlessness, economic collapse, and mass population displacement from the cities.

The RSF have destroyed or displaced most state institutions and replaced them with few new structures of their own. Rule by the RSF therefore bears little resemblance to a modern state or even a proto-state. Structurally, the RSF are a coalition of formerly state-sponsored militias, local militias, and foreign mercenaries.

Ethnically, the core of the RSF are nomadic Arabs from Sudan’s west, with Chadian Arab and non-Arab auxiliaries recruited from elsewhere in the Sahel and the Sahara, and from among Khartoum’s urban poor. Yet their tribal coalition is fractious, and the Arab tribes also have a long history of fighting each other.

Ideologically, the RSF lack a clear unifying political programme. Though many fighters are motivated by an Arabist racial ideology and local ethnic grievances (as in West Darfur, where the militias were feuding with the Masalit since before the current war), this is only an unstated part of the RSF’s programme—an element that is politically unacceptable to Sudanese as a whole and to the neighbors.

Other fighters buy into the paramilitary’s official rhetoric about overthrowing a corrupt and dictatorial regime that has long marginalized Sudan’s west. Others are drawn to the personality cult around the leader, Mohamad Hamdan Dagalo. Others are fighting out of necessity, because it is one of few options for earning a living, and they know no other profession.

Still others are drawn from afar by the lure of loot, glory, and power.

Yesterday a group from Sudan’s far west announced its arrival in Khartoum. Hailing from the Tamazouj 3rd Front armed group, they were mobilized in Um Dukhun, which straddles the border between the Central African Republic and Darfur.

In a video, the commander said they came to Khartoum “to lift the injustice against the hamish,” an ethno-political word that refers to marginalized people, especially Westerners. “We say to Mohamad Ali Qureishi, head of the Third Front, these are your troops, and we say to General Mohamed Hamadan Dagalo (inaudible, cheering)... and I bring good news to the troops here, from today, the date of your arrival in Khartoum State, you are now on the front lines of progress.”

The area where this group was mobilized is one of fluid national identities, where nomadic pastoralism is common, and where the Arab tribes have a history of involvement in RCA politics. The RSF exert influence across the border into RCA, making it likely that some of these fighters are Central African in origin. Notably, some of them wear the red berets that were part of RSF’s uniforms before the war, but which the Arab RSF soldiers of Darfur have mostly abandoned in favor of the kadmoul turban, which has greater cultural symbolism.

Another convoy of new recruits is reportedly en route to central Sudan via Wadi Howar, which crosses North Darfur and North Kordofan. The group, seen in a video, speak at least three languages: the first soldier is chanting in a non-Arabic language, the cameraman speaks in Sudanese Arabic, and another fighter speaks in French [1:33].

Probably the group includes some Chadians, as well as Darfuris or Darfuris who grew up in the refugee camps in Chad. They claim to be on their way to Port Sudan. Although this claim may be false, it possibly indicates that they were promised loot should the RSF succeed in capturing and sacking Port Sudan.

Lastly, RSF sources recently claimed that fighters of a group formerly based in Libya, the Revolutionary Awakening Council, had joined the RSF. This is unconfirmed, however, and the leader of the group, Musa Hilal, has not aligned himself with the RSF. The video of the group dates to early September.

In addition to these three examples, many groups of militia fighters traveled from Darfur to Khartoum in the early months of the war, reinforcing the large body of men that RSF already had mobilized in the capital prior to the outbreak of fighting.

For now, therefore, the flow of fighters clearly is still from west to east, into the urban core of Sudan. Nevertheless, this could easily reverse.

If the RSF’s military efforts in central Sudan stall out, there is a risk that they could turn west. Some fighters will return to their villages in Darfur, where it will be difficult or impossible to make a living because the desertification, now compounded by the ongoing economic collapse at both local and national levels.

At that point, the RSF coalition may break down as the Arab tribes turn on each other and on the non-Arab tribes. This already happened in Kubum, where the Beni Halba and Salamat burned each other’s villages and fought pitched battles killing hundreds.

Other fighters will return to Central Africa, Chad, and Niger, laden with heavier weaponry than before, enriched by loot, and radicalized by war.

This is a danger to which the sleeping governments of the Sahel and West Africa have not yet awoken. The RSF is a huge and ravenous military machine, which is unsustainable without the petrodollars that created and sustained it. Presently, it can subsist without its historic state patronage only because it is still feeding on the carcass of the vast capital city that it has ravaged. Yet a lion can be sated from one kill only for so long; after a time, it must move on to the next prey.