Thousands killed and others escape in chaotic rout of El Fasher defenders

RSF fighters film ethnic killings and boast over war crimes

The Battle of El Fasher ended abruptly and brutally on Sunday, October 26, 2025, after an 18-month siege. The Rapid Support Forces (RSF), victorious over the war-gutted city, slaughtered survivors who tried to flee or hide.

The victims included civilians, soldiers, and ex-combatants. The killings occurred at hospitals, in the streets, and on the outskirts of the city, as the RSF targeted escape routes. In general, the RSF allowed women and children to leave, while targeting the men.

The massacres followed the abrupt abandonment of the city by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), which had defended El Fasher in cooperation with local militias and the allied Joint Force. SAF defenders, running low on ammunition and supplies after months of relentless attacks, attempted to flee.

Elements of the exhausted garrison, as well as top state officials, successfully escaped in convoys of combat vehicles. Reports differ as to whether they struck a deal to secure their safe passage, fought their way to safety, or snuck out at night. Those who were left behind were killed in neighborhoods of El Fasher or on the outskirts of the city while trying to flee on foot.

“International humanitarian law is very clear: All civilians must be treated with humanity and spared from any harm. This includes former combatants who have laid down their arms and are no longer taking part in hostilities,”

— Patrick Youssef, Red Cross Regional Director for Africa

Located in arid scrublands at the edge of the Sahara Desert, El Fasher is the capital of North Darfur State. Its population is mostly Muslim and speaks Arabic. It had a pre-war population of approximately 1.1 million, 62% of whom had already fled prior to the RSF takeover, according to UN estimates.

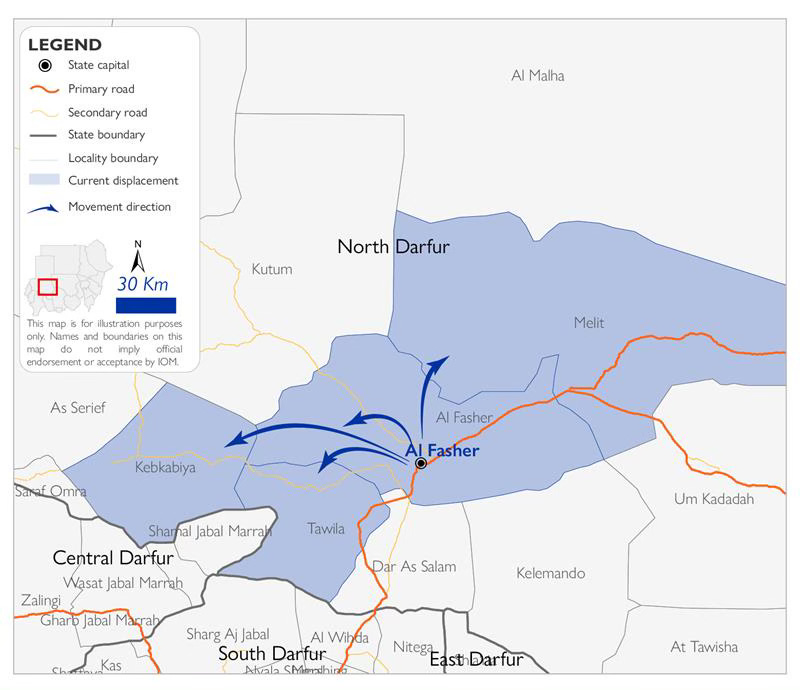

An additional 36,000 individuals fled El Fasher between 26 and 29 October 2025, the International Organization for Migration reported. They traveled on foot toward Tawila, Melit, Kebkabiya, and other destinations. Many of them arrived wounded, hungry, and dehydrated—bringing stories of terror, violence, and missing loved ones.

Doctors Without Borders, which has a medical team in Tawila, 60 km from El Fasher, reported “a massive influx of people escaping the city. On October 27 alone, MSF treated over 250 patients at the health post at the town’s entrance, including many malnourished children, pregnant women in critical condition, and dozens injured by gunfire or violence.”

Death Toll in the Thousands

Evidence of the atrocities in El Fasher comes from three main sources: (1) Emerging survivor accounts; (2) Satellite images of massacre sites; (2) Videos filmed by the perpetrators and disseminated on social media or in private chat groups. These gruesome videos, which show hundreds of bodies, likely represent only a fraction of the total incidents that occurred.

Based on the available evidence, which is still emerging and being analyzed, Sudan War Monitor preliminarily estimates that the death toll is in the thousands (3,000 or more). This total includes both combatant casualties, who were killed during the final battle for the city or while trying to escape, and non-combatant casualties, including civilians and soldiers who had put down their weapons and taken off their uniforms.

Researchers at Yale University’s Humanitarian Research Lab (HRL) reached similar conclusions. “We’re watching Rwanda-level mass extermination of people who are trapped inside,” said Nathaniel Raymond, executive director of the research group, in comments to AFP news agency. “The level, speed and totality of violence in Darfur is unlike anything I’ve seen.” Unlike in Rwanda, however, the RSF do not appear to have systematically killed women and children, though they did loot, harass, and rape some of them.

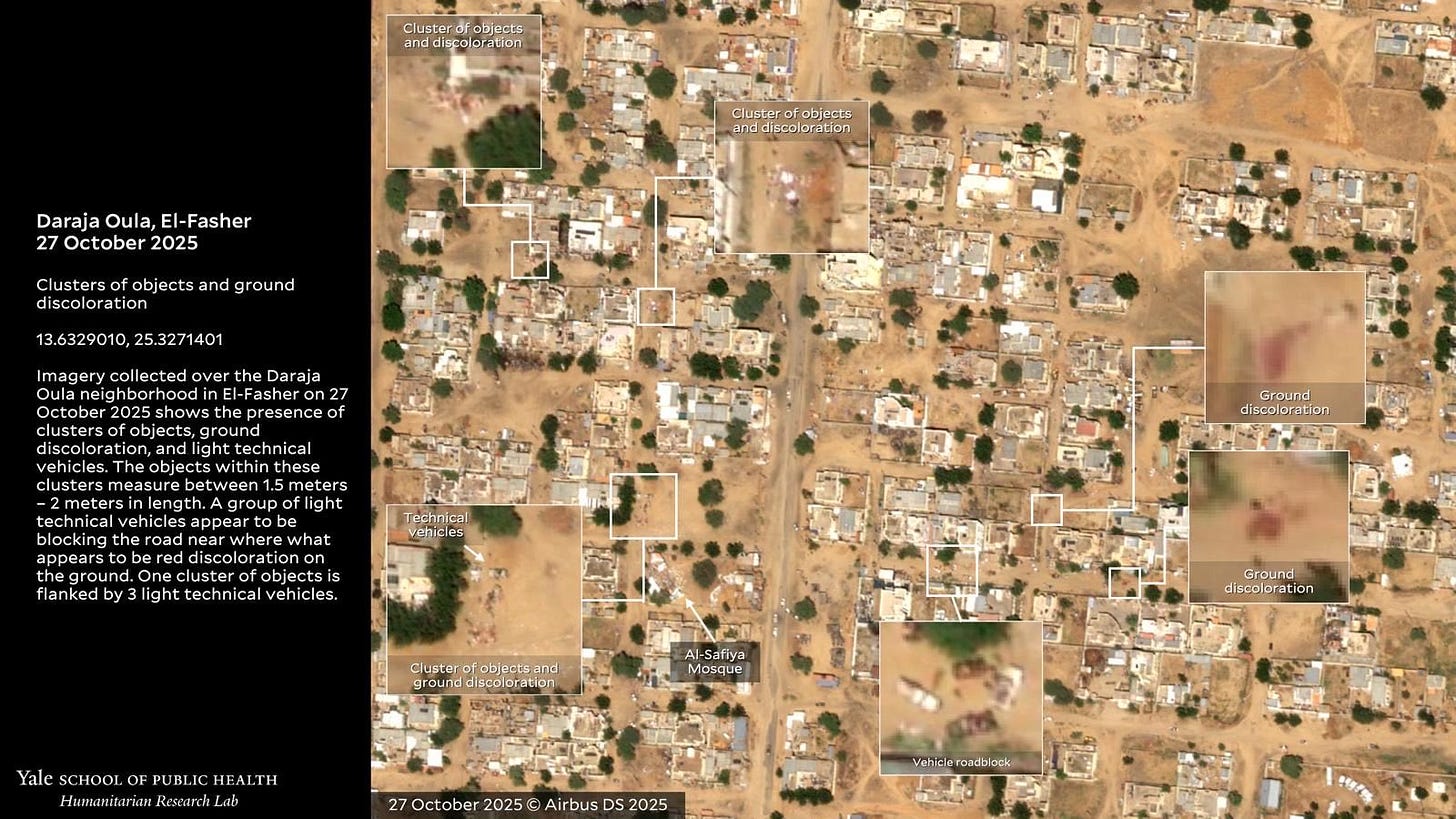

Satellite photos analyzed by Yale HRL show clusters of bodies in the city, with bloodstains literally visible from outer space. These massacre sites, combined with witness testimonies, and video evidence of killings at other locations, point to a high death toll and a pattern of systematic killing.

In brief, we summarize preliminary findings of some incidents that occurred:

A video filmed on the outskirts of El Fasher shows RSF gunmen executing ten seated men at close range, after accusing them of belonging to the army or allied militias.·Another video shows a group of seven detainees being forced to say that they are not civilians, then shot dead.

Families traveling together were separated, men from women. Ikram Abdelhameed, who escaped El Fasher with her three children, told Reuters that RSF soldiers stopped fleeing civilians at an earthen barrier at the edge of the city. “They lined the men up, they said, ‘We want the soldiers.’ They shot them in front of us, they shot them in the street.”

Another survivor who escaped the city told the BBC Arabic service, “The situation in El Fasher is extremely dire and there are violations taking place on the roads, including looting and shooting, with no distinction made between young or old.” He said he arrived safely in Tawila after a journey on foot, sleeping on the roads along the way.

RSF soldiers killed patients inside El Fasher’s Saudi Maternity Hospital, according to videos circulated by the perpetrators. One clip shows about a dozen bodies on the floor, as an RSF soldier shoots an elderly survivor. World Health Organization Director Tedros Ghebreyesus said he was “appalled and deeply shocked by reports of the tragic killing of more than 460 patients and companions at Saudi Maternity Hospital in El Fasher.”

A mass of bodies was also observed on the grounds of the Children’s Hospital, according to Yale HRL analysis of satellite imagery. The RSF had been using this abandoned health facility as a detention site.

The UN Human Rights Office in Geneva said it received reports that heavy artillery shelling from 22 to 26 October caused numerous civilian deaths, including of local humanitarian volunteers. It noted, “It is difficult to estimate the number of civilian casualties at this point, given communications cuts and the large number of people fleeing.”

A convoy of SAF-allied vehicles was ambushed 9 km northeast of El Fasher, attempting to escape on the day the city fell. Burn marks two kilometers in length were seen on satellite images. Sudan War Monitor reviewed videos of burning combat vehicles and at least 50 dead combatants at this location alone, filmed by RSF soldiers.

A large group of men fleeing on foot were chased by RSF combat vehicles and fired upon, 1 km north of the former UNAMID Supercamp, according to geolocated drone footage. Note that the below video features TikTok-style background music and propagandistic voice over.

Bodies were observed on the grounds of the Red Crescent Society office in El Fasher, according to Yale HRL analysis of satellite imagery.

Reddish discoloration of the ground, consistent with blood, as well as clusters of objects with the dimensions of human bodies, were observed in satellite images of Daraja Oula and other neighborhood of El Fasher.

Responding to reports of these crimes, the RSF-led political coalition Tasis said Tuesday it would form a committee to verify the authenticity of videos and allegations, adding that many of the videos are “fabricated” by the army.

Sudan War Monitor is a collaborative of journalists and open source researchers tracking the events of Sudan’s war and the search for solutions. We’re building a platform to battle disinformation and warmongering and amplify the voices of victims, humanitarians and peacemakers.

Background: Who Are the RSF?

The Rapid Support Forces are an umbrella group of Arab tribal militias, colloquially called the Janjaweed. Originally armed and funded by the dictator Omar al-Bashir as part of a counter-insurgency campaign in Darfur, they were formalized as a state paramilitary in 2013 and given a broader national security remit. They mutinied in 2023, triggering the current civil war. The RSF has received support from the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which opposes Sudan’s military-led government because of its close ties to Islamist political parties, including the leaders and successors of Bashir’s National Islamic Front, later rebranded as the National Congress Party.

The RSF’s constituent militias committed many ethnic killings during the last Darfur war, particularly in its early phase from 2003-2005. They also became known for crimes of sexual violence against women and girls. The same fighters, and their sons, are again perpetrating atrocities in Darfur, this time as part of an even larger national conflict.

The Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) has declared that it won’t negotiate with the RSF and vowed to eradicate it militarily. Over the past year, SAF won a string of victories, during which it committed atrocities of its own, targeting many civilians alleged to have supported the RSF. The offensive drove the RSF out of central Sudan and back to Darfur and Kordofan.

But SAF’s offensive has since stalled. The fall of El Fasher this week is the most significant military defeat for the Sudanese government in over a year—as well as a humanitarian and human rights disaster. More than a year ago, the UN Security Council passed a resolution demanding that the RSF halt the siege of El Fasher, and called for de-escalation, safe passage for civilians and humanitarian aid, and a local ceasefire. This appeal went unheeded. Instead, the RSF repeatedly assaulted the city, prioritizing its capture even at the cost of many fighters and territorial losses elsewhere in Sudan.

Political Implications

The capture of El Fasher gives the RSF control of all five state capitals of the Darfur region. The city was the historic seat of the Darfur sultanate, and it is still referred to as “Al Fasher Al Sultan,” an indication of its regional preeminence. The RSF have viewed the capture of El Fasher as a key objective in their quest for regional dominance and the legitimization of their recently established “Government of Peace and Unity.”

Additionally, El Fasher was an easy target for the RSF. They could mobilize fighters from their nearby home areas, whereas the SAF had difficulty resupplying and reinforcing the city, since it was distant and cut off from other SAF-controlled regions. In practical terms, the elimination of resistance in El Fasher allows the RSF to better concentrate its forces against the principal threats from the north and east. That could result in fresh attacks in the Dar Zaghawa region of North Darfur, and in the frontline states of West, South, and North Kordofan. The RSF have already recently retaken territory in North Kordofan, after earlier retreating from most of the state.

Meanwhile, the government of Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan, SAF Commander-in-Chief, faces mounting public criticism. During the first year of the war (April 2023 to mid-2024), public confidence in Burhan’s government plummeted, along with military morale, before recovering over the past year. The latest military setbacks revive questions about Burhan’s legitimacy and competence, which were widely voiced in 2024.

Finally, the fall of El Fasher could have major repercussions for the Joint Force, a coalition of ex-rebel groups from Darfur, recruited mostly from the Zaghawa tribe. The alliance between Sudan’s army and the Joint Force was always one of convenience, not conviction, and it may now come under strain. Notably, it was SAF’s desperation to defend El Fasher—after a series of other Darfuri cities had fallen to the RSF—that first catalyzed their alliance.

Before the siege of El Fasher, the Joint Force had remained neutral, but in April 2024, as the siege began, it declared war on the RSF. In return, the Joint Force received weapons, funds, vehicles, and access to training camps. Its ranks swelled with new recruits over the past 1.5 year, many of them trained in eastern Sudan rather than Darfur, where the force originated. El Fasher, however, remained the base of many of its veteran fighters and commanders, as well as the scene of the fiercest fighting. It is unclear how many Joint Force troops were killed or managed to escape in the latest fighting.

In a speech Tuesday evening, the Joint Force’s overall leader, Minni Minawi, sought to deflect blame for the military disaster, claiming that foreign intelligence agencies interfered in battlefield communications. While acknowledging mistakes and failures, he said,

“El Fasher would not have fallen if not for the aggressor nations mobilizing all material, logistical, and intelligence capabilities — to the point that they enlisted intelligence services in the region to jam all satellite communication devices, severing contact between the fighting forces in El Fasher and the command centers in other cities.”

Minawi vowed to continue the fight against the RSF: “This is an existential battle that does not stop at the fall of one city.”

SAF and Joint Force Survivors Flee Toward Chad

RSF forces advanced from multiple directions early Sunday and entered the 6th Infantry Division headquarters in central El Fasher with little resistance. Verified videos reviewed and geolocated by Sudan War Monitor show RSF fighters celebrating inside the compound shortly after its capture.

In previous battles, RSF forces often filmed captured weapons and ammunition depots as trophies of war. However, this time no such footage has appeared, suggesting that some withdrawing SAF units evacuated with their equipment in a coordinated manner. Clashes erupted at several locations north of the city, including at Jebel Wana, which lies along SAF’s likely escape route, 25 km northwest of El Fasher.

Below: Video of RSF soldiers celebrate after ambushing a convoy of SAF-allied vehicles, 9 km northwest of El Fasher, 26 October 2025:

Darfur24, quoting two sources in North Darfur, reported that top Sudanese army commanders, leaders of the Joint Force, the North Darfur governor, and several members of his cabinet had left El Fasher two days before the RSF announced it had seized the 6th Infantry Division headquarters.

The sources confirmed that the withdrawing forces regrouped in the town of Kornoi, located about 200 kilometers northwest of El Fasher, while the governor reached the border town of Tina.

According to these accounts, the senior command of the army—including the division commander, his deputy, the intelligence chief, the operations commander, and the heads of engineering and air defense—departed El-Fasher on Friday in three separate convoys heading toward Kornoi.

Other senior military figures, including Joint Force commanders Lt. Gen. Juma’a Hagar, Lt. Gen. Al-Tijani Duhaib, Lt. Gen. Abboud Adam Khater, and Maj. Gen. Hamid Jazm, left in an independent column.

Sudan War Monitor is a collaborative of journalists and open source researchers tracking the events of Sudan’s war and the search for solutions. We’re building a platform to battle disinformation and warmongering and amplify the voices of victims, humanitarians and peacemakers.

Army Chief Says He Approved Withdrawal

In a televised statement on Monday, Sudanese army chief Gen. Abdelfattah al-Burhan acknowledged the fall of El-Fasher while attempting to portray the military disaster as an orchestrated withdrawal. He said he had approved the withdrawal to prevent further destruction and civilian casualties.

He said, “The [military] leadership there, in assessing security, decided that they had to leave the city… They were able — and God helped them — to withdraw the city’s defenders to a safe place so as to spare the remaining citizens and the rest of the city from further destruction.”

However, Al-Burhan’s portrayal of the retreat as one that was planned and well-organized, downplays the chaos and desperation in El Fasher in recent days. As previously mentioned, hundreds of fighters were left behind. Shortages of fuel and vehicles likely meant that not all of El Fasher’s defenders could be evacuated. Many were abandoned on the frontline without ammunition, medical supplies, or food.

Internal divisions and suspicions within the ranks of SAF and its allies, the need for operational security around the evacuation, and communication problems, probably affected the evacuation effort.

Al-Burhan vowed to continue the fight, saying, “We repeat what we always say: the Sudanese people will prevail, and the Sudanese Armed Forces will prevail because they are backed by the people…. We say this people will win and this struggle will turn out in favor of the Sudanese people.”

Al-Burhan’s government has consistently refused negotiations since 2023, even when the RSF leadership has accepted to sit down for negotiations.

Humanitarian Disaster

The fall of El Fasher has worsened a humanitarian disaster inside the city and the surrounding region. Parts of North Darfur were already suffering famine, due to the war, which triggered economic collapse and displacement.

Humanitarian organizations are working in parts of Darfur, operating medical clinics, issuing cash assistance, and distributing food. But their operations are limited by bureaucratic restrictions, budget constraints, and security concerns. Sudanese authorities yesterday declared two World Food Programme officials persona non grata, forcing them to leave the country.

At a digital press briefing Tuesday, Jacqueline Wilma Parlevliet, the head of the UNHCR sub-office in Port Sudan, said that few humanitarians have ever seen a situation so dire. “It is of an extent that people have rarely seen in their long careers as humanitarian workers,” she said, citing “widespread ethnically and politically motivated killing.”

“We need peace, we need a ceasefire, we need humanitarian corridors.”