Introducing the "Popular Resistance Factions"

New militant group emerges in Omdurman

A new group calling itself the Sudanese Popular Resistance Factions has emerged in the past few weeks, rapidly developing a large online following, and publishing videos filmed near the frontline in Omdurman.

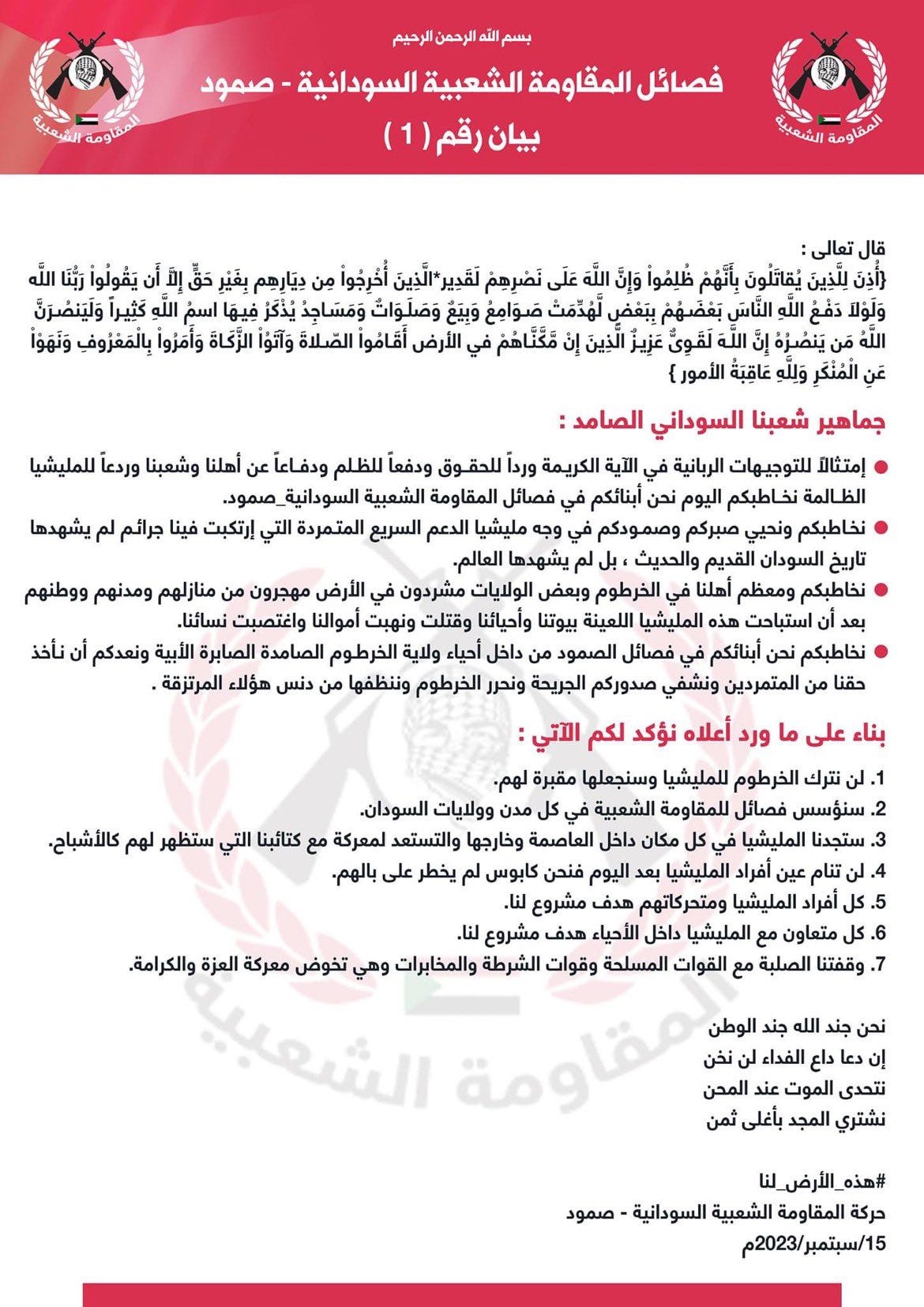

In the group’s most recent video September 18, masked gunmen presented a founding manifesto (“Statement Number 1”), introducing the group and its objectives.

Addressed to the Sudanese people, the statement begins with a quotation from the Quran before listing a litany of crimes of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and promising to “liberate Khartoum and cleanse it of the filth of these mercenaries.”

“We will not leave Khartoum to the militia, and we will make it a graveyard for them. We will establish popular resistance factions in all cities and states of Sudan. The militia will find us everywhere inside and outside the capital, preparing for battle with our brigades, which will appear to them like ghosts.”

Three things are noteworthy about the name of the group (فصائل المقاومة الشعبية السودانية). First, “Popular Resistance Factions” is similar to the name of a Palestinian armed group, the “Popular Resistance Committees” (لجان المقاومة الشعبية), operating in the Gaza Strip. This group broke away from Fatah in 2000 and is critical of Palestinian Authority’s “conciliatory” approach to Israel.

Secondly, in the Sudanese context, the word “resistance” consciously evokes the “resistance committees” that played a central role in the 2018-2019 revolution, which led to the ouster of President Omar al-Bashir. Unlike those committees, however, this group espouses violence rather than non-violence, and it emerged not from the grassroots but from the shadows.

Thirdly, the use of the word “popular” (شعبية, which can also be translated “people’s”) echoes the name of the Popular Defense Forces (PDF), a paramilitary force active during the Bashir years, with close ties to the former ruling National Islamic Front. Members of the PDF fought alongside the regular forces and were called “mujahideen,” which means “those engaged in jihad,” or holy war. The statement by the group draws upon the same historic lexicon as the PDF, concluding with this quotation from the national anthem:

“We are soldiers of God, the soldiers of the nation,

If someone calls for help, we will not betray,

We defy death during times of adversity,

We buy glory at the highest price (i.e., martyrdom).”

Like the original PDF, this new group proposes to fight alongside the regular forces as auxiliaries: “Our solid stance is with the armed forces, police forces, and intelligence forces as they fight the battle of pride and dignity.”

Officially, however, the Popular Defense Forces were dissolved in 2019 and al-Burhan’s regime hasn’t announced the formation of any successor. Nor are the Sudan Armed Forces likely to recognize any new paramilitaries for the time being because their rallying cry now is “One Army, One People”—a slogan that implicitly calls for the dissolution of any independent paramilitaries, in particular the RSF.

So, what are the ‘Popular Resistance Factions,’ and what official status do they have, if any?

Several explanations are possible, not all of them mutually exclusive. First, the creation of the group potentially is indeed intended as a step toward reestablishing the PDF, albeit in an unofficial or semi-sanctioned way. Perhaps it represents an initiative of former PDF commanders who have come out of retirement.

In that case, it would operate in much the same way as the currently active al-Bara’ ibn-Malik battalion, an Islamist group fighting alongside SAF in Khartoum and Omdurman. That battalion isn’t officially sanctioned, but its role is tacitly accepted.

A second possibility is that these new “resistance factions” are more of an information operation than a real independent force. The group’s rhetoric aligns with other pro-SAF propaganda efforts promoting the idea of a total mobilization of the citizenry in opposition to the RSF. For example, the group in its manifesto refers to itself as “your sons… from within the proud neighborhoods of Khartoum State.” In the videos, the speakers call themselves “citizens”—not soldiers.

The ‘Sudanese Popular Resistance Factions,’ in other words, are meant to be seen as grassroots, spontaneous collectives—much like the Resistance Committees of the 2018-19 protests, albeit very different in political orientation and purpose.

The group promotes a total-war, for-us-or-against-us view of the conflict, which rejects the possibility that citizens can be neutral. In its founding statement, the group hinted at targeting civilians that it deems disloyal, writing, “All militia members are a legitimate target for us. Every collaborator with the militia inside the neighborhoods is a target for us.” Similarly, in this video the speaker says that those who have fled the country rather than staying to fight should not come back:

After watching this video, I observed that the same man appeared in a video released by the General Intelligence Service (formerly NISS) Operations Authority. From this we can conclude that the Sudanese Popular Resistance Factions either share members with the intelligence service, or the group is just a front for the intelligence service.

As I said earlier, however, these explanations are not mutually exclusive. Even if the new group is merely a ‘front’ for the General Intelligence Service, it still could eventually develop its own distinct identity, command structure, and membership.

Lastly, the new ‘Resistance Factions’ might consist in part of members of the Sudan Shield militia established before the current war. This is conjecture, based on the fact that the new group calls one of its subdivisions the ‘Shield Brigade.’ For background, Sudan Shield was formed in December 2022 amid mounting tensions between the army and RSF. It was meant to serve as a bulwark in support of SAF, but its commander Abu Aqlah Kikel defected to the RSF, leaving the group leaderless. Although Kikel claimed that all his troops joined the RSF too, that is likely not true.

Therefore, for those who remained loyal to SAF, a rebrand would make sense at this stage. The timing of the events supports this hypothesis. Kikel announced his defection in August, and the Sudanese Popular Resistance Factions announced itself in September.

Whatever the case, the group represents a new brand of militancy. It operates outside the law and without official sanction. Who will be its ultimate victims… just the Rapid Support Forces—or perhaps innocent citizens too?