Understanding the fighting in El Fasher

Battle for North Darfur capital is causing a major humanitarian crisis

Fighting in and around the North Darfur capital El Fasher has killed hundreds of people in recent weeks and forced thousands to flee, amid warnings of an impending famine that could kill thousands more.

More than 700 casualties arrived at the South Hospital in El Fasher from May 10-20, of which 85 died of their wounds, according to Doctors Without Borders. Additional deaths were reported by other sources, and the MSF toll doesn’t include combatant and civilian casualties that were not brought to the hospital.

The besieged city is running out of food, fuel, and medical supplies, amplifying the suffering of residents, who have few places to run or hide.

El Fasher is where the 2003-2020 war in Darfur began. Today it is a critical battleground in a 13-month war that shows no signs of stopping any time soon. It is the historic seat of the Fur Sultanate, the capital of the Darfur Region and one of the largest city’s in Africa’s Sahel zone, the semi-arid region bordering the Sahara.

Control of El Fasher is symbolically and practically important for Sudan’s army as it is its last remaining foothold in Darfur, the home region of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary originally formed by nomadic Darfur Arabs—particularly those of the Rizeigat tribe—which is now battling for control of the entire country.

For many years the RSF enjoyed the support of the Sudanese state and the RSF’s leader Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo backed army leaders who carried out a coup in 2021, toppling a civilian-led government. But after talks last year to disband the RSF and integrate it into the Sudanese military, the RSF rebelled and rapidly took over most of the capital Khartoum and large parts of western Sudan.

After a string of defeats in Darfur last year, the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) bolstered its defenses around El Fasher by striking a deal with a coalition of formerly neutral armed groups, the Joint Force of Armed Struggle Movements, which had thousands of troops in El Fasher. The Joint Force in November declared that El Fasher was a ‘red line’ and announced they would go to war with the RSF if that line was crossed.

For several months, the RSF generally respected this ultimatum.

That began to change in March and April this year after several of the Joint Force groups—specifically SLM-MM and JEM (Jibril Ibrahim faction)—graduated several battalions of new recruits in eastern Sudan (an area controlled by the army), and committed these troops to participating in SAF offensives in central Sudan.

The fragile local truce in North Darfur soon collapsed, the Joint Force outright declared war on the RSF, and the RSF attacked and burned villages belonging to the Zaghawa, the ethnic group of the Joint Force leaders and many of its troops.

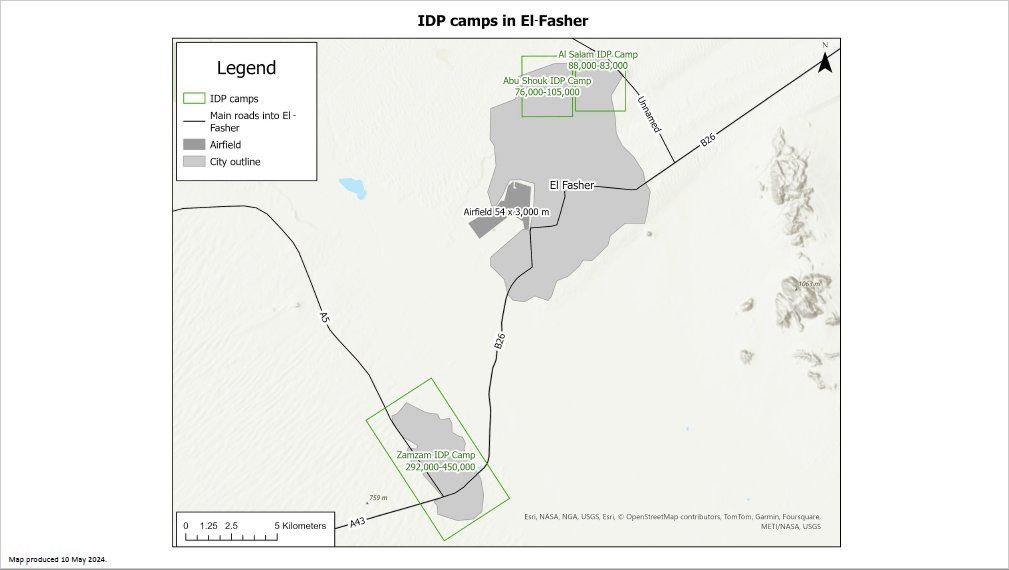

By mid-April the RSF had mobilized thousands of troops toward El Fasher and surrounded the city. Clashes have been ongoing in parts of the city ever since then, particularly in the northern and eastern parts of the city and its outskirts.

This past week’s fighting devastated parts of the Abu Shouk Camp (pictured in the video above), which is home to about 100,000 people who fled during the Darfur genocide in the early 2000s. Among those killed in the crossfire was Sajida Abdullah Al-Mouli (picture below), a volunteer with the Abu Shouk Emergency Room, who worked at the El Fasher South Hospital.

Residents of Abu Shouk are living in a “constant state of terror” due to shelling by the RSF, a resident told Radio Dabanga. He said a shell fell today on two shelters in the camp, injuring several people, including children. Speaking with the BBC, another El Fasher resident said he lost his brother in the fighting and couldn’t bury him because the fighting was too intense. “I had to abandon my brother's body on my way to the cemetery,” said Mohamed Haroon Abdallah.

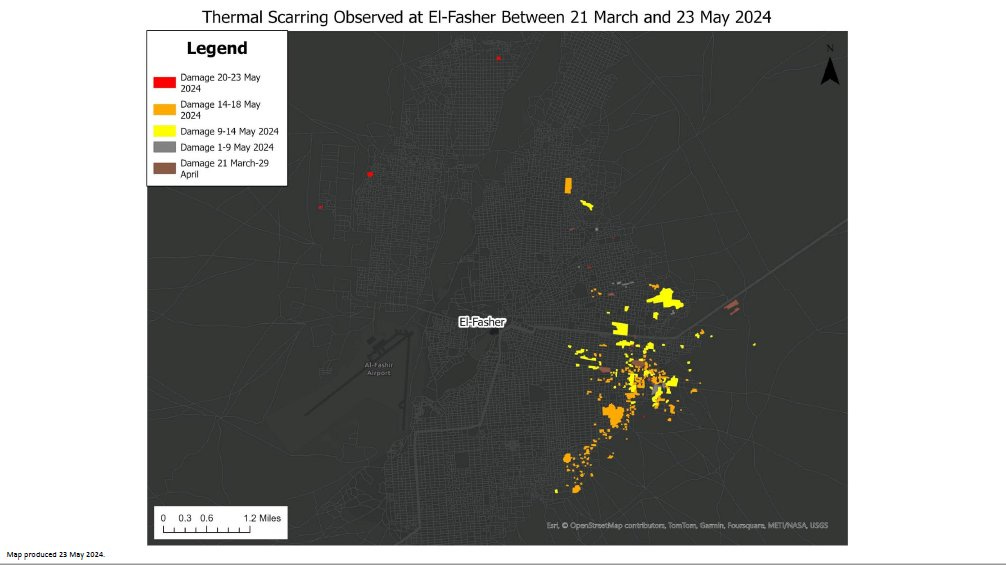

The Yale Humanitarian Research Lab (HRL), which is carrying out an open source monitoring project for Sudan, on Thursday released a report about the latest fighting in Abu Shouk, highlighting the threat to civilian lives. The report stated:

“Yale HRL identifies conflict-related thermal scarring within northern and western areas of Abu Shouk IDP camp between 22 and 23 May 2024. The damage in these locations is consistent with an expansion of the fighting in El-Fasher, including RSF ground penetration into Abu Shouk IDP Camp on or around 23 May 2024. The current presence of RSF forces in Abu Shouk IDP camp cannot be confirmed.

“Open sources have reported that there is fighting between RSF and SAF-aligned forces near the Mellit Gate area with bombardments and small arms the morning of 22 May 2024. Open sources have also claimed that RSF has allegedly beaten, tortured, and extrajudicially detained displaced persons and civilians and looted their belongings in Abu Shouk Camp.

“… RSF and SAF combat in and around Abu Shouk represents a major deterioration in the human security situation inside and around El-Fasher. The events documented by Yale HRL in and around Abu Shouk in recent days are the first confirmed incidents of an IDP camp near El-Fasher being directly affected on a large scale by RSF’s current offensive operations in El-Fasher. While sporadic incidents have been reported involving RSF and SAF as early as December 2023 in Abu Shouk, the damage to civilian structures, combined with open source reporting of RSF engaging in alleged human rights abuses of civilians, is a critical development. Unchecked, more damage and casualties inside Abu Shouk camp should be expected in the immediate future.”

Yale HRL stated that the fighting in Abu Suouk “ indicates the opening of a northwestern front in RSF’s multidirectional assault on the city.”

By contrast, most of the fighting last week was on the eastern side of the city in the vicinity of the power plant, which the Sudan Armed Forces bombed on Monday after losing control of it, as seen in this video produced by the RSF.

Conflict outlook

Militarily, the situation in El Fasher could be described as a “siege,” but it differs from sieges in other Sudanese cities last year, such as Nyala and Jebel Aulia, in that the El Fasher garrison is much larger and has more mobility, fuel, and firepower, enabling it to project power beyond its bases toward the city’s outskirts and beyond.

These capabilities are due in large part to the involvement of the Joint Force, which consists of veteran fighters from the previous civil war who fight in a hit-and-run style similar to the RSF’s own fighting style.

The 6th Infantry Division, headquartered in the city center, is larger than the infantry divisions in other parts of Darfur that were overrun last year, having recruited thousands of new men locally and absorbed defectors from other groups, as well as survivors of brigade headquarters overrun in other parts of the North Darfur last year.

Another factor is that large parts of the local population support the army and the Joint Force, rather than the RSF, similar to the situation in El Obeid, where another large infantry division has survived RSF attacks since last year despite the city being largely cut off from the rest of the Sudanese army.

Unlike El Obeid, however, El Fasher is largely cut off from commercial traffic and humanitarian aid. The World Food Programme has positioned resources in Chad that it could bring into Darfur via the Tina border crossing, but bureaucratic impediments and insecurity have prevented WFP from reaching most of the people in need.

In order to bolster El Fasher’s defenses, the Sudan Armed Forces have diverted resources from other theaters, hampering planned counter-offensives to retake the capital Khartoum and the central Sudanese city Wad Madani. In particular, SAF has dedicated a lot of its limited military aviation resources to carrying out airstrikes in North Darfur and resupplying El Fasher using airdrops.

The latest airstrikes took place in cities near El Fasher controlled by the RSF, including Kabkabiya and Kutum. The strike in Kabkabiya on Wednesday, video of which we geolocated, killed at three civilians and as many as nine, according to media reports.

War goals

For the RSF, success in El Fasher would mean, at minimum, containing SAF to the city. Darfur is the RSF’s home base and main recruiting ground; it’s where they have their families. So it’s important for them to prevent operations by the SAF and Joint Force outside of El Fasher, which could hamstring the RSF’s larger national ambitions.

More ambitiously, the complete capture of the city would boost the morale of the RSF troops, discourage resistance in other areas, provide plunder to reward fighters, and free up thousands of fighters for operations in central Sudan.

On the other hand, for the Sudan Armed Forces, success in El Fasher means repelling the RSF onslaught, breaking the siege, resupplying the city, and eventually extending control beyond the capital to other parts of Darfur. If the SAF can break the power of the RSF in one or more decisive battles, it would be easier to encourage factionalism and defections from the paramilitary, eventually loosening their hold over Darfur.

Another possible war goal is to slaughter the livestock belonging to the Arab tribes that have supported the RSF, potentially inducing famine. A recent aerial attack in Melit, north of El Fasher, which killed hundreds of camels, points to this emerging strategy. Similar attacks on livestock have taken place near El Obeid and Babanusa.

In Brief

A court in Gedaref sentenced a man to death by hanging for allegedly for sending information to the RSF about the positions of the military forces based in Gedaref.

Journalists in Port Sudan told Radio Tamazuj that they are harassed by security personnel and cannot operate easily in the city. Sudan’s news media sector has largely collapsed except for some journalists working for foreign satellite channels, digital media, and some local broadcasters. The print press has ceased.

A “popular delegation supporting the Juba negotiations with the SPLM led by Abdulaziz Al-Hilu” held a press conference in Port Sudan on Thursday, state-run SUNA reported. The group of civic leaders led by Dr. Hassan Abdel Hamid Al-Nur complained of the high prices of essential goods in army-controlled cities n South Kordofan, including Dilling and Kadugli. The development highlights the pressure for a deal with SPLM-N despite the recent collapse of humanitarian talks.

Vice President of the Transitional Sovereignty Council Malik Agar arrived in Asmara on Thursday to participate in Eritrea’s National Day and hold talks with President Isaias Afwerki. Eritrea is one of Sudan’s few regional allies.

The director of the Joanna Amal Rest House, which specializes in caring for child cancer patients, warned of child deaths due disruptions to their treatment. The initiative is working to set up a new rest house in Merowe.