Why Colombian Mercenaries Are Fighting in Sudan

Mohamed bin Zayed’s Misadventure in Sudan

“History is a jangle of accidents, blunders, surprises and absurdities, and so is our knowledge of it, but if we are to report it at all we must impose some order upon it.”

— Henry S. Commager (1902-1998), historian and essayist

ANALYSIS

Colombian mercenaries are now fighting in Sudan’s civil war, their mission shaped by the ambitions of a distant autocrat. It feels as improbable as a forgotten episode from the 1860s, when Sudanese-born soldiers fought in Mexico for the French emperor Napoleon III. In each case, the soldiers were drawn into someone else’s war — and into a conflict their employers neither fully understood nor ultimately controlled.

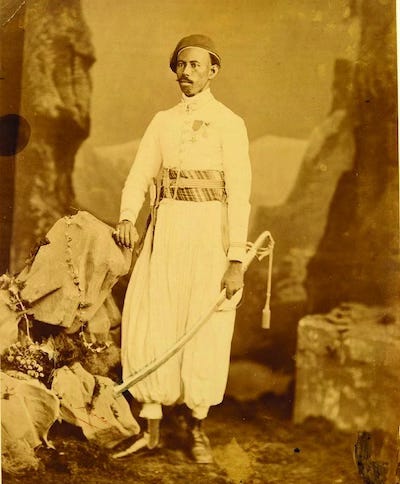

In 1863, a battalion of Sudanese soldiers arrived in Mexico as part of an ill-fated French invasion. These men, originally slaves in the Egyptian Army under the Khedive Sa’id Pasha, were contracted by French military officials, who were convinced that African soldiers were resistant to tropical diseases like yellow fever and malaria.

The French deployed their Sudanese troops to Veracruz, a tropical lowland region rife with disease. The Sudanese remained in Mexico for four years, alongside tens of thousands of French and imperial troops. The history of this force — known to the French as “le bataillon nègre égyptien” — is detailed in the 2023 book Ordinary Sudan, 1504–2019. It is a story of slavery, race, war, ideology, and ill-conceived military adventurism.

The idea of conquering Mexico took root in the restless mind of Emperor Napoleon III, who clung to illusions of imperial grandeur — of achieving military glory in the vein of his uncle, the great conqueror Napoleon I. Unable to challenge Europe’s major powers, he turned his gaze to distant Mexico, then weakened by civil war.

Napoleon III knew nothing of Mexico. He was an effete socialite who had no military experience, unlike his uncle. Yet he had an army at his disposal, and Mexico was vulnerable. Napoleon framed the invasion as a civilizational mission. As one historian noted, “Napoleon III and his advisors… regarded Mexicans as members of an inferior, child-like race who needed a monarchist government and European civilization to escape from the chaos that had engulfed them on independence.”1

These ideas collapsed in the face of military and political reality. After six years, Mexican nationalist forces, backed by the United States, drove out the French and executed the Hapsburg archduke whom the French had installed as “Emperor of Mexico.” The Sudanese battalion, reduced from 446 men to 299, was among the last of the imperial forces to leave Mexico, returning to Egypt and then Sudan in 1867.

This was perhaps the only time in history that Sudanese soldiers clashed with Latin American troops — until now.

MBZ: Little Napoleon of the Arabian Gulf

One hundred and fifty-seven years later, an equally out-of-touch, over-ambitious monarch, Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), has embarked on a foreign military escapade as fantastical as the French occupation of Mexico. Since 2023, the Emirati ruler — widely known as MBZ — has led a covert intervention in Sudan, funding and arming the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a regional militia that mutinied against the Sudanese government and triggered the current war.

The UAE’s latest effort involves deploying a Colombian mercenary force — reportedly several hundred strong — to eastern Libya and Darfur. These soldiers, veterans of Colombia’s decades-long internal conflict, have conducted both training missions and direct combat operations. Verified videos show Colombian fighters operating in El Fasher and Zamzam Camp, famine-hit areas where heavy fighting has raged.

The Latin Americans’ 2025 deployment to Sudan reverses the 1863 precedent, when Sudanese troops fought in Latin America. Yet both historical episodes are explainable in connection with the grandiose aspirations and ideological views of the monarchs behind them. MBZ and his lieutenants view the Sudanese war as part of a regional ideological struggle between the anti-Western Muslim Brotherhood and the religiously liberal, mercantilist monarchies of the Gulf.

Explaining the RSF-UAE Alliance

The RSF, led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (“Hemedti”), emerged from the notorious Janjaweed militias of Darfur. Recruited largely from nomadic Arab tribes in Darfur and Kordofan, the RSF’s culture revolves around warfare, camel-herding traditions, and a racial ideology rooted in the region’s history of slavery. For Emirati elites, who live ensconced in gleaming high-rises and luxury mansions, far removed from their desert heritage, the RSF represents a purer form of Arabism than their own, one that evokes an idealized image of their own past.

Officially, the UAE government denies supporting the RSF, but key Emirati journalists, foreign policy leaders, and influencers either implicitly or explicitly defend the intervention in Sudan, portraying the RSF as a counterweight to the country’s Islamist-backed military regime. Though both the Emiratis and their RSF clients are Muslims, they practice a less legalistic faith than the hardline adherents of the Muslim Brotherhood, who are influential in central Sudan.

Despite the RSF’s complicity in horrific war crimes and a coup that toppled Sudan’s democratic government in 2021, the UAE has promoted the renegade paramilitary as a democratic alternative to Sudan’s Islamist military regime. The RSF’s Emirati handlers know full well that the RSF are brutal authoritarians, not democrats, but they don’t care; they admire the RSF for the damage that they have done to the Sudanese government, for their willingness to fight, and for the cultural affinities that they share.

Before Sudan’s civil war, the UAE had already deployed RSF fighters abroad as mercenaries: in Libya on behalf of Khalifa Haftar’s forces, and in Yemen against the Houthis. In both cases, the RSF acted as a proxy ground force in conflicts where the UAE wanted influence but minimal Emirati casualties.

The UAE Doubles Down

Having long relied on the RSF as proxies abroad, the Emiratis were unwilling to watch their allies collapse at home. During the first year of the war, the RSF captured major cities and army bases across western and central Sudan, appearing almost unstoppable. But by late 2024, the tide turned: the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) launched a sustained counter-offensive that steadily eroded RSF control. Losses mounted, troops began deserting or feuding with each other, and the RSF grew politically isolated both internationally and domestically.

At this point, the UAE might have cut its losses and abandoned its floundering ally. After all, the war in Sudan does not directly threaten UAE interests, so the Emiratis could walk away at any time. Instead, they doubled down. They supplied long-range strike drones used to attack fuel depots, dams, and electricity stations in army-controlled areas. They facilitated RSF logistics hubs in neighboring countries, provided anti-aircraft weapons, and helped orchestrate the formation of a coalition of opposition groups, led by the RSF, that declared itself a parallel government.

The arrival of Colombian private military contractors in early 2025 marked another escalation. While some have been used as trainers and convoy security, others have joined RSF combat units in Darfur and Kordofan, bolstering RSF assaults on contested cities such as An-Nahud in West Kordofan and El Fasher in North Darfur.

Below: Footage of Colombian fighters engaged in combat alongside RSF troops, and evacuating a wounded fighter. Likely in El Fasher, North Darfur.

Collectively, these efforts largely succeeded in halting the Sudanese army’s momentum. Sudan is now effectively partitioned. The SAF controls the Nile Valley heartland, the Red Sea coast, and parts of Kordofan and Darfur. The RSF dominates most of Darfur and roughly half of Kordofan. Beyond Sudan, the RSF also controls smuggling routes and operates recruitment networks in Chad, the Central African Republic, eastern Libya, and parts of South Sudan — all countries where the UAE has courted influence, using its vast oil wealth to sway corrupt leaders.

As fighting rages in Sudan, the distant emir of Abu Dhabi is detached and indifferent to the immense suffering that he has helped to sow. Like the obtuse Napoleon III, the French ruler who busied himself with a grand reconstruction of Paris while Mexicans endured years of unnecessary warfare, Mohamed bin Zayed preoccupies himself with flashy projects in his glittering capital while Sudan disintegrates.

Like the French folly in Mexico, the Emirati venture in Sudan has not produced triumph, only a grinding stalemate. The two sides persistently raid and withdraw, while SAF jets batter RSF-held towns, producing mass civilian casualties but little movement on the map.

Counterproductive Strategy

The Emiratis are not wrong about Islamist influence in Sudan’s government. Yet they fail to see that their militarist policy undermines their own goal of weakening the Muslim Brotherhood. By fueling the war, rather than helping to broker an end to it, the UAE has contributed to a dangerous polarization among the Sudanese people.

The UAE’s intervention is widely resented among Sudanese, even among critics of the military junta, stirring nationalist and even extremist sentiment. Sudan today is more militarized, xenophobic, and ideologically polarized than at any time since the 1990s. Millions of Sudanese who did not support the junta have rallied behind it, preferring this to the alternative of RSF rule. Large numbers of boys and men from all backgrounds — secular leftists, moderate Islamists, Christians, and others — are now at training camps run by Islamist ideologues, fueling the proliferation of the very ideology the UAE claims to oppose.

Even if the RSF could recapture the capital Khartoum and unseat the government, it could not effectively govern the Nile Valley and eastern regions. Its record of administration in the territories it controls has been dismal, and it lacks political legitimacy both domestically and internationally. Insurgencies would inevitably emerge in the cities of the Nile Valley, eventually driving the RSF back to Darfur.

For all the UAE’s escalations, there are hard limits to what hired soldiers can achieve in Sudan. Foreign mercenaries, no matter how skilled, cannot decide the war’s outcome. The Colombians may tip the scales of a battle, but they cannot change the nature of the RSF, an ungovernable paramilitary, incapable of governing others.

This does not mean, however, that the RSF will be easily defeated. Sudan’s military has lost much of the momentum it had earlier this year, the economy is in dire straits, famine is spreading, and internal divisions within the army and its coalition — the seeds of future conflicts — lie just under the surface.

The Cost of Foreign Folly

The French adventure in Mexico brought no gain to France and years of suffering to Mexico. The Emirati adventure in Sudan risks the same — enriching contractors and arms dealers while impoverishing and destabilizing millions. Mohamed bin Zayed probably will take a few more years before he realizes the futility of his government’s bizarre venture in Sudan. When he does, the Emiratis will abandon the RSF, just as Napoleon III abandoned Mexico in 1867, evacuating his Sudanese battalion and the rest of his army after a long and unnecessary war.

Sudan’s history suggests that the war will end either through negotiation or mutual exhaustion and collapse. Until then, Sudanese civilians will bear the brunt — and foreign mercenaries will keep fighting, and dying, in a war far from home, for Emirati gold.

Heather J. Sharkey, “The Sudanese Soldiers Who Went to Mexico (1863–1867): A Global History from the Nile Valley to North America”, in Elena Vezzadini, Iris Seri-Hersch, Lucie Revilla, Anaël Poussier and Mahassin Abdul Jalil (eds.), Ordinary Sudan, 1504–2019, Berlin/Boston, Walter De Gruyter, 2023, p. 214.