Introductory Guide to Sudan's War: Who, What, Where and Why

Straightforward answers to basic questions, plus in-depth nuance and context

This guide is intended for readers seeking to understand the war in Sudan, particularly those who have limited or no prior knowledge. If you find it useful, please consider sharing it to support wider awareness of the conflict.

In Brief

What’s Happening? War, famine, atrocities, a repressive political environment nationwide, and the largest refugee crisis in the world.

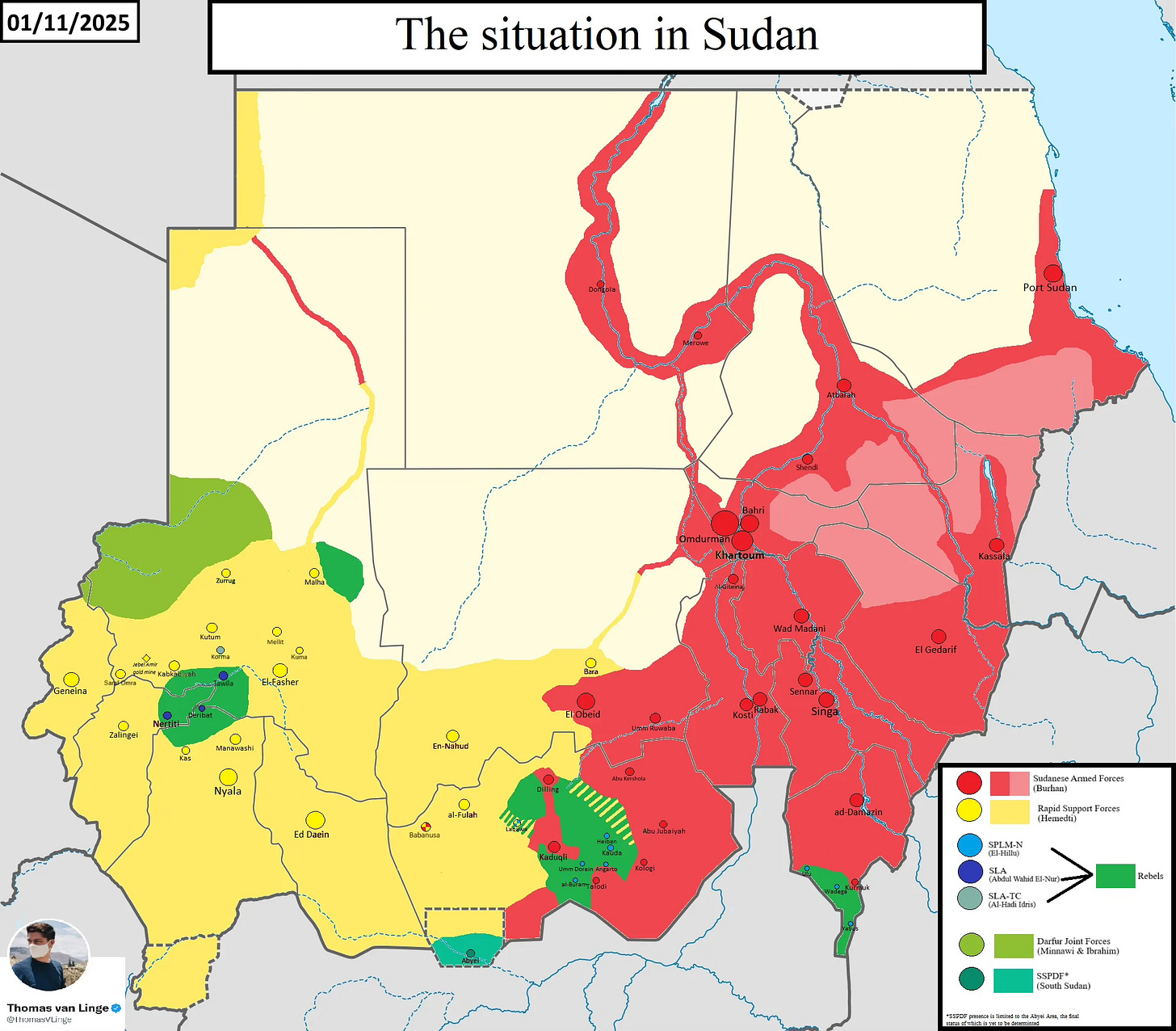

Where Is This War? Sudan was once the largest country in Africa, until the independence of South Sudan in 2011. Fighting began in the capital, Khartoum, in 2023, intensified along the Nile Valley in 2024, and shifted west toward the arid regions of Darfur and Kordofan in 2025.

Who is Fighting?

Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) — The national military, shaped by decades of authoritarian rule and now controlled by a military junta.

Rapid Support Forces (RSF) — A coalition of Sudanese Arab militias (often described as a paramilitary) originating in Darfur and West Kordofan. Formerly aligned with the military, the RSF became independently powerful and mutinied in 2023, triggering the civil war.

Why Are They Fighting? Motivations include power, money, ideology, nationalism, and ethnic hatred. There is also the internal logic of a prolonged war: years of fighting, mass atrocities, and heavy losses on both sides have fueled a cycle of revenge and open calls for extermination of the enemy. Even Sudanese who desperately want the war to end struggle to imagine what peace or coexistence might look like.

The Outside Backers:

Egypt and Turkey are key supporters of the Sudanese military, providing both political backing and practical assistance. Iran also supplied the SAF with weapons, though its support has ended.

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is the leading supplier of the RSF, providing attack drones, armored cars, medical treatment for wounded combatants, and financing entire mercenary units.

Chad has played a more passive but still critical role by allowing RSF rear-area operations on its territory, including recruitment, military logistics, and economic activities. Kenya, while officially neutral, has permitted the RSF to conduct political organizing within its borders.

The Warring Parties: An Overview

Sudan’s war is primarily a struggle between two major armed groups, the SAF and the RSF. Smaller factions play a secondary but still significant role.

Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF): “One People, One Army”

The national military, commanded by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, controls most of northern, central, and eastern Sudan from its base in Port Sudan. The SAF portrays itself as the guardian of national unity and state authority—defending the country from collapse and disorder. Though it lacks a democratic mandate, Sudan’s military regime argues for its legitimacy on the basis of necessity and national crisis.

SAF is numerically superior to the RSF and relies more on defensive tactics, fixed positional warfare, aerial bombing, and limited, carefully planned offensive operations. SAF has proved itself more capable than the RSF in long-term urban combat environments, but it has struggled with maneuver, tactical flexibility, and long-distance logistics in remote rural areas.

SAF consists of the Army, Air Force, and Navy. It is supported by several paramilitaries, including the Central Reserve Police, Sudan Shield, the Operations Authority of the General Intelligence Service, and the Al-Baraa Ibn Malik Brigade (an unofficial but powerful Islamist paramilitary). Additionally, SAF has relied on contracted mercenary aviation assets.

Rapid Support Forces (RSF): “Victory or Death”

The RSF is a paramilitary created by a previous dictator (Omar al-Bashir) to help suppress rebellions in the country’s western Darfur region and in the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan.

Al-Bashir’s government constituted the RSF from local militias recruited among the pastoralist, Arab-identifying tribes of Darfur and Kordofan, including the Rizeigat, Misseriya, Beni Halba, Salamat, and Ta’isha. Colloquially called the “Janjaweed,” these militias were implicated in genocidal violence against non-Arab tribes of Darfur in the early 2000s. They played a central role in defeating Darfuri rebel groups militarily.

Initially, the Bashir regime armed and paid the Janjaweed militias covertly through the military intelligence service. However, the RSF acquired legal status as a national paramilitary in 2014. Subsequently, the RSF grew in size and power, even as the conflicts in Darfur and Kordofan died down. They fought as mercenaries in Yemen for the UAE, and also in Libya.

The RSF is led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, a long-time Rizeigat militia leader from a camel-herding background.

The RSF prefers maneuver warfare, mounting its troops in modified pickup trucks with heavy guns (‘technicals’) and armored cars. Additionally, they employ attack drones for surveillance, long-range strategic attacks, and urban combat operations. The RSF finances itself through smuggling, gold mining, extortion, pillage, and the external backing of the UAE.

Together with allied political groups, the RSF formed a political alliance, known as Ta’sis (Establishment/Founding), which has declared the creation of a rival government to administer territory under RSF control. Known as the Government of Peace and National Unity, this entity has not achieved any international recognition.

Allied and Neutral Groups

Several rebel and non-aligned armed groups were already active in Sudan prior to the outbreak of the current war. Each group has its own command structure, ethnic base, and foreign ties.

Joint Force of Armed Struggle Movements (JFASM): A coalition of Darfur rebel groups that signed the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement, led by Minni Arko Minnawi. The Joint Force stayed neutral for the first year of the war before declaring war on the RSF and allying with SAF in early 2024. It played a central role in the 18-month siege of El Fasher, repulsing dozens of RSF attacks, until the eventual fall of the city in October 2025. The Joint Force consists of two main groups, JEM and SLM-Minawi, plus a handful of small factions. The majority of its forces are ethnic Zaghawa.

Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N): Led by Abdel Aziz al-Hilu, the SPLM-North historically had close ties politically and militarily with the guerrilla movement that became the ruling party of South Sudan (SPLM). It controls the Nuba Mountains and consists mostly of ethnic Nuba, a term for a variety of non-Arab tribes of South Kordofan State. SPLM-N formed an alliance with the RSF in early 2025 and is currently besieging the cities of Kadugli and Dilling.

Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLA-AW): Led by long-time exile Abdelwahid Al-Nur, this faction controls the Jebel Marra highlands of central Darfur. It is neutral in the war and its territory has served as a safe haven for thousands of people fleeing from elsewhere in Darfur. Its leadership and the majority of its soldiers are ethnic Fur.

Sudan Liberation Movement – Transitional Council (SLM-TC): Led by Al-Hadi Idriss and active in North Darfur, this group initially stayed neutral before splitting, with some men joining SAF and others joining the Ta’sis Alliance led by the RSF.

Who is Winning the War?

Nobody is winning. The country as a whole is losing.

Throughout the conflict, both sides have claimed to have the upper hand and predicted imminent total victory. Consistently, these predictions have turned out to be false, as the tides of war have ebbed and flowed.

For the first year and half of the war (April 2023-August 2024), the RSF defeated SAF many times in battle, seizing vast territories in western and central Sudan and taking control of most of the capital. The launch of a multi-front SAF counteroffensive in September 2024 culminated in the recapture of Khartoum and its sister city Omdurman by May 2025.

SAF’s momentum waned in mid-2025 as the war shifted closer to the RSF’s strongholds in Darfur and West Kordofan. In the meantime, the RSF intensified its siege of El Fasher, the final SAF-held city in Darfur, and employed new long-range drones to attack critical targets, both civilian and military, undermining morale and public trust in the Sudanese military.

The fall of El Fasher in October 2025, following an 18-month siege, marked a major setback for SAF. Subsequently, the RSF also attacked a SAF garrison in Babanusa, West Kordofan. Overall, the conflict appears to be a stalemate, though each side continues to search for ways to gain the upper hand.

Why Are They Fighting?

Economic, ideological, environmental, and international factors are major causes of Sudan’s ongoing war. Less often discussed is the conflict’s significant ethnic dimension. Most of the RSF are nomadic Arabs from Darfur and Kordofan, whereas the leadership of the SAF are mostly Nile Valley Arabs from cities and farming areas.

Central and eastern Sudan, the stronghold of the Sudanese military, is more developed economically and enjoyed relative peace prior to 2023. By contrast, Darfur and Kordofan are poorer, rural, and historically more violent. The RSF rank-and-file were shaped by decades of local conflict, which resulted in a warrior ethos that glorifies violence and denigrates peacetime occupations such as farming, business, and education.

Historically, Sudan’s Nile Valley Arabs held the highest rung within an established racial hierarchy. This system developed during the Turco-Egyptian and British colonial eras, before becoming entrenched after independence in 1956. It placed darker skinned Nuba, Ingessana, South Sudanese, Masalit, Fur and other non-Arab tribes at the bottom of the hierarchy. Collectively, these groups were referred to as “slaves.”

The pastoralist Arab tribes of Darfur and Kordofan, which form the core of the RSF, held a middle rank within Sudan’s historical racial hierarchy. As they grew in power in recent decades, they began to challenge the privileged position of the Nile Valley Arabs within the historical racial hierarchy. Today, RSF propagandists often denigrate Sudan’s northerners as impure (racially mixed), cowardly, and tools of the former colonial masters.

The ethnic dimensions of the conflict are not as straightforward as they were in certain other contexts, such as Rwanda in 1994. Sudan is more diverse and neither warring party is ethnically monolithic. Nevertheless, long-standing racial attitudes remain ever-present in the background of the conflict, if not always openly discussed. Both sides have carried out mass arrests and extrajudicial killings on an ethnic basis.

How Many People Have Died?

There are no reliable estimates. Civilian deaths are sometimes counted and documented, but the warring parties do not disclose their losses.

Conservatively, we estimate that at least 100,000 people have died in the conflict, though a higher toll of 150,000-200,000 is also a reasonable estimate. These figures refer only to direct conflict deaths, not excess mortality caused by conflict indirectly, such as deaths caused by malnutrition or disease outbreaks that otherwise would not have occurred.

A mortality study by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine estimated that over 61,000 people died of all causes in Khartoum State between April 2023 and June 2024, a 50% increase in the pre-war death rate. Of these, 26,024 deaths were due to intentional injuries. And that figure covers only one state and only the first 14 months of the war.

Both sides have committed atrocities against civilians as well as war crimes including executing prisoners of war and deliberate targeting of civilian markets. Many civilians have died as a result of indiscriminate aerial bombing and shelling, as well as targeted aerial attacks (launched by drones or airplanes) on civilian targets — including markets, mosques, and hospitals.

What Are the Economic Consequences?

Sudan’s gross domestic product contracted by approximately 29.4% in 2023 and another 13.5% in 2024, according to World Bank data. Inflation soared by 66% in 2023 and another 170% in 2024, as the currency collapsed.

Nationwide cereal production (sorghum, wheat, and millet) declined by more than 40% in the first year of the war, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization. Famine has gripped several parts of Darfur and Kordofan, basic services have collapsed, and many markets are closed or destroyed. Disease outbreaks, including cholera, have surged among displaced communities.

Two years of urban combat devastated the nation’s capital Khartoum and several other cities. This severely damaged the industrial sector, government sector, and financial sector, and caused millions of people to flee their homes, creating a deep economic crisis. Approximately 71% of the population lives on less than US $2.15 per day—more than double the pre-war poverty rate.

The third year of war has mostly been fought in rural areas, small towns, and the western city of El Fasher. Though this has allowed urban Sudanese to return home in some areas, the national economy remains distressed, due to inflation, militarization, and lasting damage to national economic institutions and critical infrastructure like bridges and power networks. Additionally, investor and business confidence has collapsed, meaning that economic activity is unlikely to revive even in areas where conflict has subsided.

Meanwhile, the ranks of both warring parties have swelled due to forced recruitment, widespread unemployment, and the closure of schools and universities (both sides employ teenage soldiers). An estimated 19 million Sudanese children are out of school.

When and How Did the Conflict Start?

The RSF mutinied in April 2023. They stormed the presidential palace, military airfields, and other key government sites. For this reason, critics say the RSF attempted a coup, which failed, triggering a prolonged fight for power and survival. However, the RSF counters that it was attacked first.

Both sides appear to have prepared in advance for the conflict. For background, political tensions between the SAF and the RSF began building in 2022. Each side began reinforcing its troops in the capital, resulting in growing distrust between the two sides. On April 15, 2023, fighting erupted suddenly in Khartoum, and spread quickly to other areas. Both sides claim that the other side fired the first shot.

What Kind of Government Does Sudan Have?

Sudan’s national government is controlled by a military junta, known as the “Sovereignty Council,” which took power in a coup in 2021, overthrowing the interim civilian government of Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok.

This coup accelerated the political breakdown leading to the current war. Despite this, SAF presents itself as the only force capable of maintaining order during a time of national emergency.

Many of Sudan’s generals are holdovers from the Islamist regime of Omar al-Bashir, who ruled from 1989-2019. Sudan has a civilian prime minister and cabinet appointed by the nation’s military ruler. It has no parliament. Though nominally a federal system, political power in reality is centralized, with state governments being largely or wholly dependent on the national government.

Is This a Religious Conflict?

The short answer: No, Sudan’s war is not a religious war in the usual sense of that phrase. Approximately 90% of Sudanese practice the Islamic faith or are nominally Muslim, and most soldiers on both sides of the conflict identify as Muslims. Non-religious persons, Christians, and believers in indigenous religions constitute small minorities in Sudan.

This war should not be confused with the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005), which was sometimes framed as a religious conflict because it was fought largely in South Sudan, which has a substantial Christian population.

The more nuanced answer: Religion is an important part of life in Sudan, and religious ideology and language is used by leaders on both sides to motivate soldiers, justify the violence, and console the grieving. Additionally, the religio-political ideology of the longtime ruling party, the National Islamic Front (aka National Congress Party), has influenced many officers of the Sudanese military, and plays a role in driving the conflict, according to secular Sudanese political parties opposed to the war.

The RSF claim to be fighting to rid the country of the “remnants” of this former Islamist regime, though the RSF itself was created to defend the former regime. Critics see the RSF’s anti-Islamist stance as a tactical one, designed to attract support in the Middle East, particularly from the UAE, which is a liberal Gulf monarchy that opposes Islamist political forces.

How is South Sudan Involved or Affected?

South Sudan isn’t directly involved in Sudan’s war, though various armed groups have used its territory as a safe haven and staging area, including SAF, RSF, and SPLM-N. The neutrality of South Sudan, its instability, and the nation’s culture of rampant corruption make it an important contested area for covert operations, including smuggling weapons and looted goods, evacuation of wounded combatants, repatriation of escapees from captured or besieged areas, influence operations and mercenary recruitment, etc.

South Sudan itself is deeply affected by Sudan’s war, despite its neutrality. It achieved its independence from Sudan in 2011 but it still has close economic and social ties with Sudan. It fought its own internal civil war from 2013 to 2018, leaving lasting social and economic scars.

Oil exports via pipelines in Sudan are South Sudan’s main source of GDP and government income. For about a year, the war interrupted these exports, due to damage to pipelines and the disruption of critical maintenance operations. Although exports have resumed, the severe and prolonged loss of government revenues has destabilized South Sudan’s already fragile government and amplified existing political and military tensions.

How is the War Related to the Massive Protests in Sudan a Few Years Ago?

Sudan enjoyed a period of relative peace from 2019-2023, after the Sudanese Revolution. That was a popular uprising that started in December 2018, leading to the toppling of the long-time dictator Omar al-Bashir.

Millions of pro-democracy protesters took to the streets, demanding civil rights and a more peaceful future. After months of mass protests, in April 2019 the military ousted al-Bashir, and partly turned over power to a civilian government, headed by a civilian prime minister. This civilian-led government had plans for elections and security sector reform. They made peace with some Darfur and Blue Nile rebel groups, and they put the former dictator and some of his henchmen on trial.

However, the military never fully relinquished power, and in October 2021 they carried out a counter-revolutionary coup d’état, ousting the civilian component of the government. After that, the army ruled the country in partnership with its paramilitary ally, the RSF, until the two armed services turned on each other. Unfortunately, the rivalry and ambitions of these two groups has shattered the hopes of the pro-democracy protesters.

Decades of War: What’s Different This Time?

Sudan has a complex history that involves a series of different conflicts, but also periods of relative peace. Depending how one counts, this is Sudan’s fifth civil war since independence in 1956. The previous wars include:

First Sudanese Civil War (Anyanya War): 1955-1972

Second Sudanese Civil War (SPLM War): 1983-2005

Darfur War: 2003 - 2019

SPLM-North War (Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile): 2011-2019

Historians and analysts see recurring drivers across these conflicts—economic marginalization, political exclusion, ethnic hierarchy—but also important differences. For example, the first two civil wars featured strong separatist movements, whereas the current war does not involve any separatist factions.

Another key difference is that all of the prior wars were fought in Sudan’s hinterlands. This war, by contrast, erupted in the capital Khartoum and involved sustained fighting in the nation’s Nile Valley heartland.

Urban warfare in Khartoum and its sister cities, Bahri and Omdurman—together one of Africa’s largest metropolitan areas—produced mass displacement on a scale unprecedented in Sudan’s history.

Finally, this war carries a greater risk of state collapse than any previous conflict. The RSF rebellion in 2023 marked a defining moment in Sudanese history. At one point in 2024, the RSF controlled most of Khartoum and Omdurman as well as the fertile states of Al Jazeera and Sennar, and appeared poised to topple the government. Though they have since retreated westward, the RSF remain a potent threat.

What Is Being Done to Stop Sudan’s War?

Short answer: not much.

Shine a Light on Sudan’s Crisis

Sudan War Monitor is dedicated to tracking the world’s largest humanitarian crisis and the conflict that has caused it. We’ve been able to sustain and grow this initiative thanks to a global network of supporters. You can help by upgrading to a paid subscription, which gives you access to subscriber-only extras, as well as our full archive of reporting and analysis.

Other ways you can help:

📢 Forward our newsletters to colleagues and friends.

📲 Share our work on social media.

🔗 Link to Sudan War Monitor from your website or blog.

🎁 Purchase a gift subscription for someone else.

💳 Make a one-time donation.

✍️ Leave a thoughtful comment or testimonial.