Ukraine’s Sudan gambit

What are Ukraine's political and military objectives in Sudan?

Ukrainian special forces have carried out both aerial and ground attacks in Omdurman, the sister city of Sudan’s capital Khartoum, according to a report Monday by the Kyiv Post.

A video published by the newspaper showed a group of purported Ukrainian operatives carrying out a nighttime raid into territory controlled by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Filmed using infrared imaging, the video showed an operative firing a rocket launcher at targets inside an apartment building.

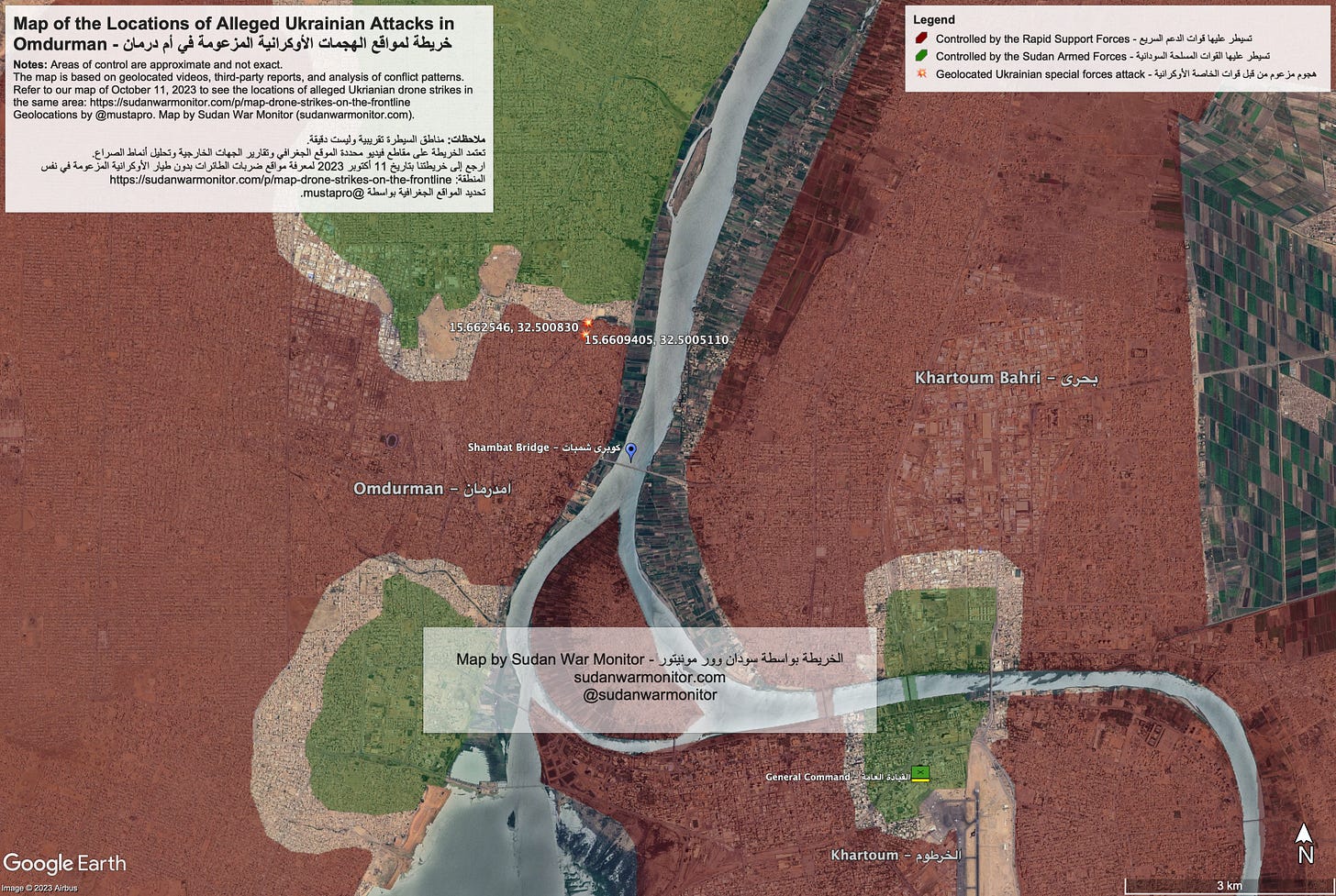

This video was geolocated to the Abu Rouf neighborhood of Omdurman, which is on the frontline between the RSF and Sudan’s army.

The targets likely were members of the RSF, which a Ukrainian security source referred to as “local terrorists” allied with the Wagner Group. “The footage probably shows the work of special units of the Main Intelligence Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine,” the Ukrainian security source told the Kyiv Post.

A second video showed a drone strike or artillery strike, also in Omdurman.

Though not a direct claim of responsibility, this is the second time Ukraine’s security services have hinted at carrying out operations in Sudan. In September, CNN published videos showing 14 attacks by “Ukrainian-style” kamikaze drones in Omdurman and its western suburb Ombada (video below).

A Ukrainian military source said, “Ukrainian special services were likely responsible.” In all the drone videos, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) were the target.

Ukraine’s political objectives

For Ukraine, these attacks—and the media leaks accompanying them—achieve the purpose of undermining the reputation of the Wagner Group in Africa.

Wagner Group has long basked in sensationalistic media coverage of its activities throughout Central Africa, giving it an aura of power and mystique. Bot networks and other influence operations have further amplified Russian propaganda in the region.

Often, the hype doesn’t live up to the reality. For example, Wagner Group has failed to suppress al-Qaeda and Islamic State militants in Mali, despite being paid $11 million per month by the Malian government in addition to concessions for mining rights.

The mercenary group, which operated as an arm of the Russian state, became leaderless in August when Yevgney Prigozhin died suspiciously in an airplane crash, just two months after he led a short-lived mutiny against the Russian president, Vladimir Putin.

Since then, Putin has moved quickly to disband the Wagner Group and take control of its operations. The Wall Street Journal reported November 3 that two Russian billionaires who are part of Putin’s “inner circle,” Arkady Rotenberg and Gennady Timchenko, are financing two new private military companies, Convoy and Redut, which will subsume Wagner Group operations in Africa.

Ukraine aims to undermine the Russian reputation before these new mercenary groups gain a foothold in Africa. By attacking Wagner allies such as the RSF, Ukraine could make other potential clients hesitant to work with Russia and its state-controlled mercenaries.

“Ukraine’s operation in Sudan is principally an information operation, and only secondarily a military operation.”

Ukrainian security chiefs might also harbor genuine animosity toward the RSF, which has smuggled gold to Russia and benefitted from anti-aircraft weapons, drones, and other equipment supplied by the Wagner Group and other Russian companies.

Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, leader of the RSF, coincidentally was visiting Russia when the invasion of Ukraine commenced in February 2022. Upon his arrival in Moscow, on the eve of the invasion, Dagalo said, “Russia has the right to defend its citizens and protect its people. This is a right guaranteed by law and the constitution.”

Overall, Ukraine’s goal is to isolate Russia diplomatically and economically as it pursues a counter-offensive to retake territory that Russia captured during the 2022 invasion. Given these political objectives, Ukraine’s operation in Sudan is principally an information operation, and only secondarily a military operation.

Ukraine can achieve substantial public relations impact at minimal cost—just a small team or two, perhaps just for a temporary assignment. To be clear, there is no concrete evidence—visual or otherwise—that the operatives seen in the videos are Ukrainian. They could be mercenaries of other nationalities. But they do not seem to be Sudanese fighters, given the difference in equipment and their light skin color.

If these operatives are Ukrainian, that would make Ukraine the only Western ally of the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF). No other Western nation has stepped in militarily to assist the Sudanese military against the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces.

At the same time, Ukraine’s decision not to officially acknowledge the operation allows the nation to avoid political repercussions should it later get cold feet about the partnership. In effect, it has claimed responsibility for these operations, while maintaining a veneer of deniability.

Military significance of the Ukrainian operation

Militarily, Ukraine’s intervention in Sudan hasn’t done much to help the Sudan Armed Forces overall. The war between SAF and the RSF is now in its seventh month, and SAF have suffered a series of defeats, at first in the capital Khartoum, and more recently in Darfur and Kordofan.

The Ukrainian military intervention is tiny in scale compared to SAF’s overall size and the vast geographic scope of the war. And of course, Ukraine has few military forces to spare for sustained operations in Sudan. It continues to battle Russia across a huge front in eastern Ukraine. Although it has gained the upper hand in that war, Ukraine is still outnumbered and faces a determined foe that could fight on for several years.

Even so, the Ukrainian intervention in Sudan could make a significant military impact over the long term, if it is sustained. In addition to the political benefits of the relationship, SAF could benefit from Ukrainian expertise in drone warfare, aviation, and artillery. Ukrainian aviation experts have worked in Sudan’s humanitarian, commercial, and peacekeeping sectors for many years.

The Ukrainian military also has become one of the world’s most experienced in urban combat, following a massive year-long battle in Bakhmut, among other cities.

The area where Ukrainian forces carried out their recent night attack—as well as most of the drone strikes—is one of the most important theatres of combat in Sudan. Only about 2 km separates SAF from the Shambat Bridge, which is the only bridge across the White Nile controlled by the RSF. Six of the alleged Ukrainian drone strikes took place on the Shambat Bridge itself.

The bridge is also about midway between SAF’s forces in northern Omdurman—its strongest concentration of forces in the country—and a besieged territory known as Corps of Engineers. Many of the army’s most elite forces are deployed in this area, so it makes sense that they would ask the Ukrainians to support them along this front.

High-level relationship

A key question is what kind of relationship the Ukrainian president has with Sudan’s military leader, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. The two held an “unscheduled meeting” at Shannon Airport in Ireland in September, after leaving the UN General Assembly meetings in New York. Zelensky said after meeting al-Burhan,

I am grateful for Sudan's consistent support of Ukraine's sovereignty and territorial integrity. We discussed common security challenges, namely the activities of illegal armed groups financed by Russia.

I invited him to support the Grain From Ukraine initiative and take part in this year's summit. We considered possible platforms for intensifying cooperation between Ukraine and African countries.

Beyond the political relationship, Zelensky and al-Burhan have something else in common, namely, each man recently spent time under siege, threatened by enemy forces. Zelensky has lived under threat of Russian attack for nearly two years, often living in an underground bunker. His decision to stay in the Ukrainian capital Kyiv was particularly risky in early 2022 before the Russian advance on the capital was checked. Likewise, the Sudanese commander-in-chief spent the first four months of Sudan’s new war at the army headquarters in Khartoum, which was surrounded by the RSF and under constant attack. Most of the army headquarters had burned down by the time Burhan was extracted from it in August.

It is likely that al-Burhan and Zelensky (or their senior aides) spoke by phone prior to their meeting in Ireland. Given that Ukraine’s operation in Sudan began in September at the latest (the CNN report was published September 20), they may have spoken in July or August. Whatever the precise origins of this new partnership, it is clear that it has high-level sanction in both governments.

Wider implications for Africa

The recent Ukrainian press leaks via CNN characterized the RSF as a “Wagner-backed militia”—despite only minimal evidence of Wagner’s involvement in Sudan since the war began in April—and no evidence that Wagner forces are actually fighting alongside the RSF. For its part, the Kyiv Post didn’t even bother mentioning the RSF, except in a background paragraph.

The Ukrainian conflation of the RSF with Wagner is interesting because it implies a potentially wide field of action by Ukrainian forces against Wagner allies in Africa. If this is the Ukrainian basis for action, then the same logic would apply to the governments of Mali, the Central African Republic and elsewhere, making them legitimate targets.

"The Ukrainian conflation of the RSF with Wagner is interesting because it implies a potentially wide field of action by Ukrainian forces against Wagner allies in Africa.”

For diplomatic reasons, Ukraine is unlikely to threaten any action against these governments, of course. Nevertheless, the Sudan operation is a significant precedent.

In Russian propaganda, Ukraine is often portrayed as a puppet of the West. And indeed, Ukraine is currently receiving huge amounts of Western military assistance. Yet Ukraine has shown it is willing to chart its own course, sometimes annoying its patrons in the West by ignoring their advice on strategy or tactics, or by carrying out aggressive covert operations such assassinations and drone strikes inside Russia.

Ukraine’s engagement with Sudan has puzzled many Western observers and governments, who would prefer to keep Sudan’s military rulers at arm’s length. Could this be the start of a new phase of Ukrainian military adventurism in Africa? Or is it an ill-conceived experiment that is unlikely to be repeated?