5 scenarios that could make the situation in Sudan dramatically worse

Egregious lack of urgency to resolve the conflict

Six months ago, a battle erupted in Sudan’s capital city, Khartoum, igniting a war that has burned unceasingly ever since. The city’s skyscrapers have gone up in flames, its downtown is utterly desolate, its markets are pillaged, and its suburbs have become a battleground where trapped residents are shot, shelled, and bombed.

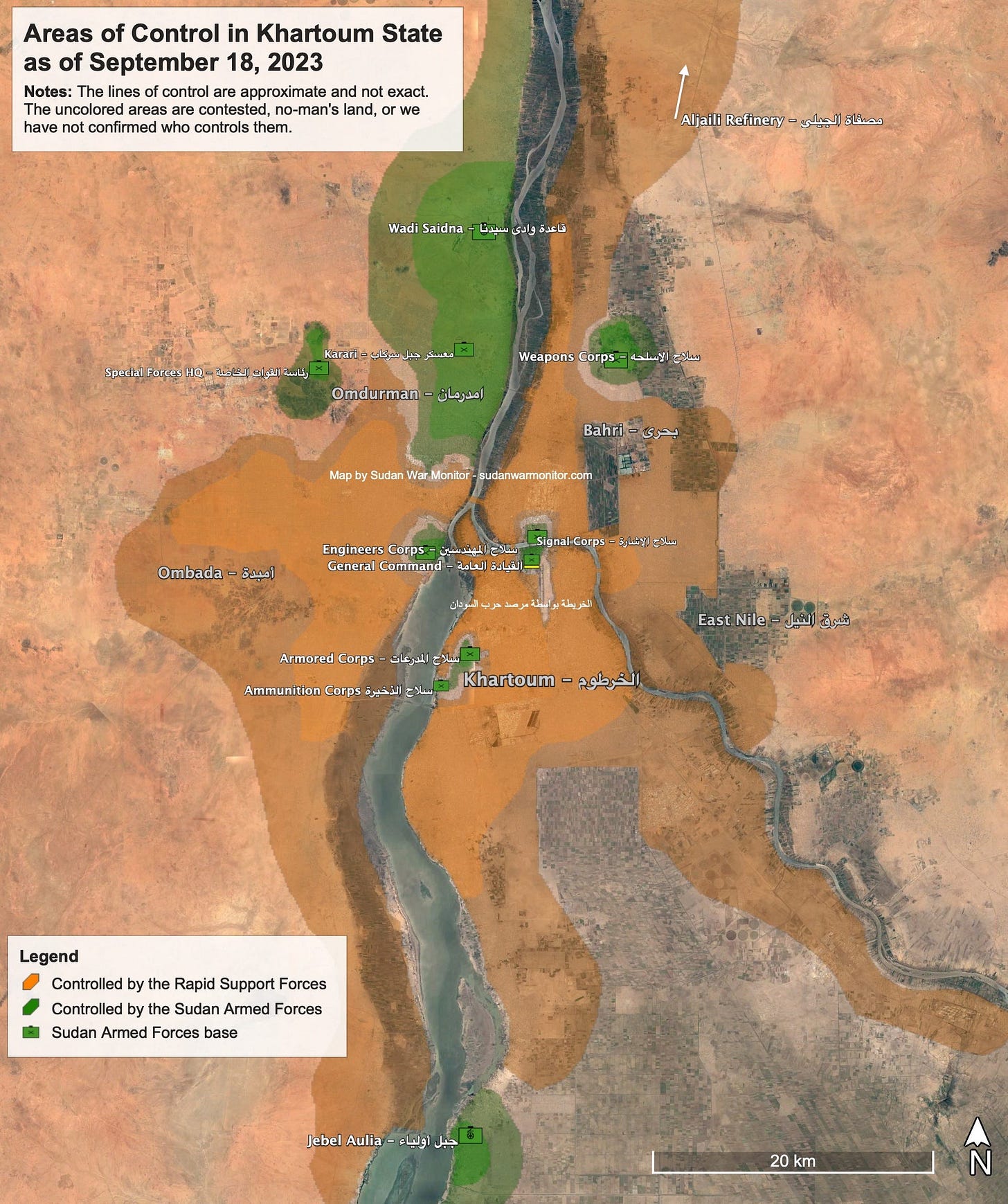

Two factions of the former military regime, the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), refuse to negotiate a ceasefire and instead are fighting street to street with near total disregard for the civilian inhabitants.

Khartoum, a revolutionary city that toppled a repressive dictatorship in 2019, is now under a brutal siege and devastating bombardment.

In Darfur, the RSF and allied Arab militias—both colloquially called “Janjaweed”—have taken the conflict as license for an ethnic rampage. They burned villages and slaughtered hundreds of people, just as their predecessor militias did in the region in the early 2000s.

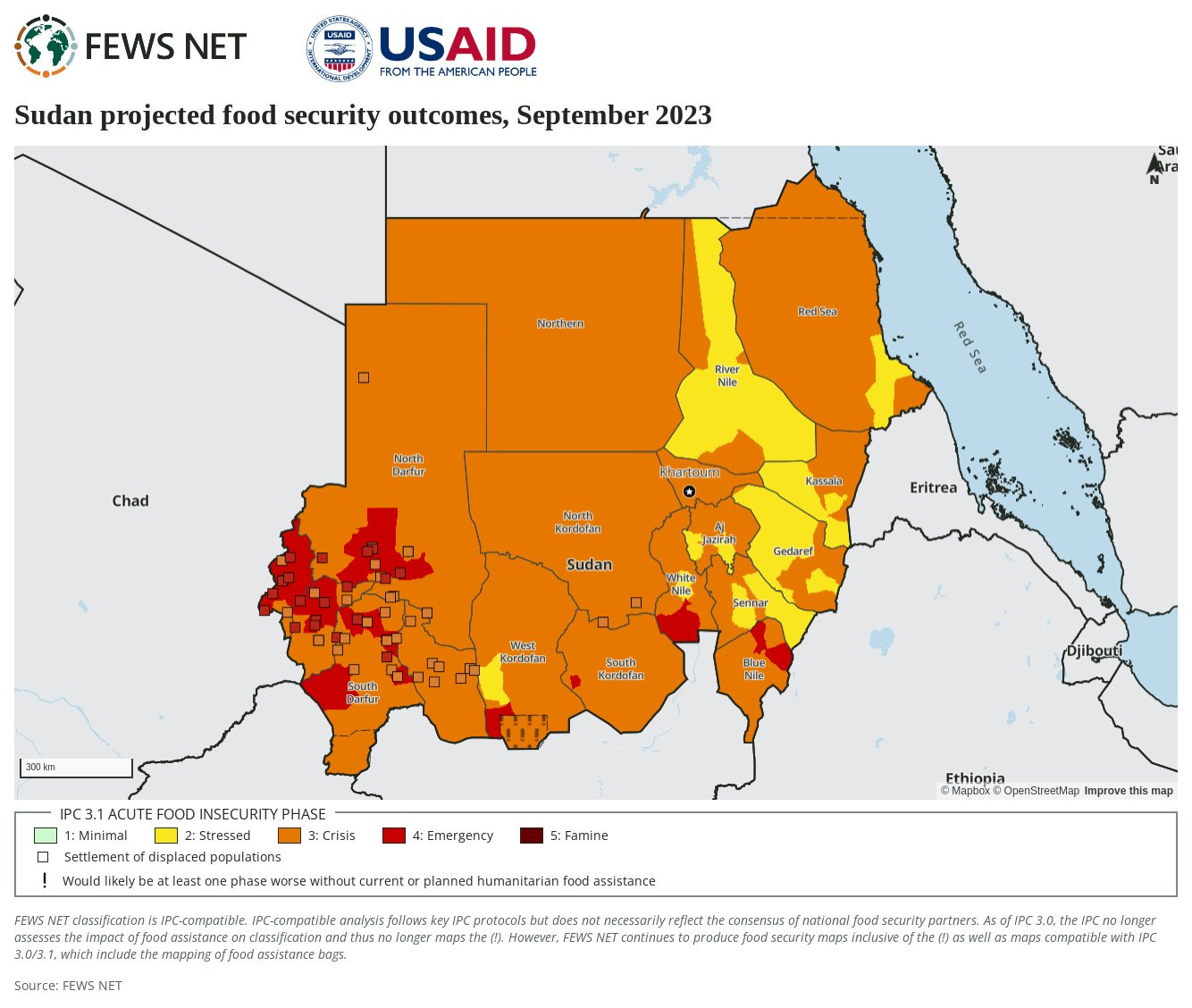

Sudan is now the world’s largest humanitarian disaster. Six million people are displaced from their homes, 19 million children are out of school, and most of the country is at Phase 3 (“crisis”) of the five-level IPC famine gauge. Parts of Darfur and some urban populations are at the pre-famine stage, Phase 4 (“emergency”).

The death toll, according to ACLED data, is more than 9,000, but the organization says this is a “conservative estimate due to methodological limitations of real-time reporting in a conflict of this nature.” The actual toll is probably at least double or triple that, in my opinion, in part because of unrecorded civilian deaths, and in part because the warring parties aren’t forthcoming about their combat casualties.

As terrible as the conflict is already, it could unfortunately get worse. There aren’t any signs that it is burning out. Instead, mass mobilization of fighters is continuing, the war is spreading to hitherto unaffected areas, and new weapons are flowing into the country. Civilian anti-war initiatives lack momentum, and there is no coherent international effort to end the conflict.

Here are five scenarios that could make the war in Sudan significantly worse. Although I’m not forecasting any of these scenarios per se, none of them is far-fetched.

Scenario #1: Oil flows are cut off

Sudan’s economy is largely in ruins, but oil production continues. Crude oil from oil fields in the country’s south and neighboring South Sudan flows north through pipelines to the Red Sea city of Port Sudan. The oil revenues serve as a lifeline for Sudan’s army, the civil service, and the surviving state and federal institutions. If the oil flows were stop, Sudan would be at risk of further state collapse.

In this scenario, South Sudan’s government would quickly run out of money too, which could trigger another civil war and another humanitarian catastrophe. The South Sudanese government, which the West had hoped would become a democracy when it won its independence in 2011, instead has devolved into an unstable military dictatorship, more dependent on oil than Sudan itself. South Sudan’s kleptocratic government survives through a mix of corrupt patronage politics and repressive tactics like controlling the press and arresting political opponents. Without oil revenue, South Sudan’s warlords will turn on each other and fight.

This could happen at any time. Militarily, the RSF are able to cut oil flows with ease. Recently, they took control of a key pump station at al-’Aylafun, as seen in the below video, and they could also attack the pipelines at other places.

The fact that they have not done so suggests that the RSF have a direct relationship with the Chinese and Malaysian firms that control oil production in Sudan. They may be receiving some kind of protection money in return for keeping the oil flowing. Politically, the RSF also hope to take power, at which point they will benefit from the oil revenues more directly.

But that political calculus might not last forever. If the RSF suffer military setbacks, for example, they could be tempted to try to cripple the Sudan Armed Forces financially by cutting the oil flows.

Scenario #2: The Sudan Liberation Army enters the war

Darfur’s former rebels, foremost of which are the Sudan Liberation Army faction of Minni Minawi, have stayed neutral in the current war. They control the North Darfur capital of El Fasher and other parts of Darfur, where Minawi is regional governor under the terms of a peace agreement signed after the Sudanese revolution in 2020.

SLA and the other former rebels see nothing to gain from joining one side or the other in the current war. They fought both the RSF and SAF for many years, and distrust them both. But circumstances could eventually force their hand. Attacks by the RSF on commercial convoys escorted by the former rebels, for example—or attacks on Fur or Zaghawa villages—could provoke them into a wider conflict.

If this were to happen, the level of violence in Darfur would escalate dramatically, including in previously unaffected villages and cities.

Scenario #3: Genocidal violence, which hitherto mostly targeted the Masalit, is turned on other Darfur tribes

This scenario could happen in conjunction with Scenario #2. So far, the worst ethnic violence has been in West Darfur, where the RSF and affiliated Arab militias targeted principally the Masalit and Erenga, calling them dogs and slaves as they raped the women and exterminated male members of these tribes as young as one year old.

However, the other two largest ethnic groups in Darfur, the Fur and the Zaghawa, have not been systematically targeted as they were during the Darfur genocide that began in 2003. This is partly because the armed groups most associated with these ethnicities—SLA and JEM—have remained neutral.

There have been incidents of racist violence, and many Fur and Zaghawa still live in displacement camps or refugee camps in neighboring Chad as result of that earlier conflict. Fortunately, so far, large-scale attacks against them have not happened.

Yet recent threats by the RSF to attack new areas underscore the risk of further genocidal violence. Last week, the RSF and affiliated militias began mobilizing in al-Geneina and threatening to invade Kulbus Locality, in which case the Gimir tribe residing in that area would be at risk of mass atrocities.

Scenario #4: RSF attack another major urban area

The bulk of the RSF fighting force is currently in the capital region, Khartoum. The paramilitary scored military victories in the capital early in the war and has sought to consolidate its position ever since. But the final pockets of resistance are heavily fortified, and the army has succeeded in reinforcing its troops in Omdurman.

This dynamic has kept the war so far mostly contained to Darfur, Kordofan, and the central capital region, while the east and north have been spared.

Nonetheless, the RSF have tens of thousands of troops in Khartoum, which could deploy elsewhere on short notice. Recent attacks on Jebel Aulia and al-’Aylafun, south of Khartoum, as well as reported advances in rural areas of Jezira State, underscore the risk of the war spreading.

Perhaps the cities at greatest risk are al-Obeid, which is surrounded by the RSF, and the cities nearest to Khartoum, such as Wad Madani and Shendi. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, the commander of the RSF, has threatened to carry the war as far east as Port Sudan. This is unlikely, for the time being, but indicative of his ambitions.

Needless to say, if fighting spreads into another major urban area, hundreds of thousands more people could be displaced, and the disaster would worsen.

Scenario #5: A global economic recession sharply curtails humanitarian funding even as needs continue to increase

The global economy is slowing and there is a risk that it could tip into recession. If that were to happen, it would likely curtail international donations for humanitarian operations, including from both private donors and the major sovereign donors.

At the same time, the number and severity of conflicts in the world is increasing. In a briefing earlier this year, United Nations officials stated, “the world is facing the highest number of violent conflicts since the Second World War”—and that was before the outbreak of war in Sudan and the latest conflict in Israel and Palestine.

In the entire Sahel-Sahara region, the Horn of Africa, and the Middle East, there are now only a handful of countries that aren’t suffering from serious internal conflict.

Sudan used to host as many as one million refugees and asylum-seekers from nearby states, including Ethiopia, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Eritrea. Now many of them are forced to flee again. For example, the remarkable man in this video, Okomo, fled from South Sudan to Ethiopia, from Ethiopia to Khartoum, and finally from Khartoum to Port Sudan.

Humanitarians in Sudan are already warning of a mismatch between the level of humanitarian need and the resources available. “Many Sudanese residents feel angry and abandoned, as relief efforts fall short compared to the level of suffering,” said Patrick Youssef, ICRC’s regional director for Africa, in a statement yesterday.

“Keep Sudan in your prayers, please. Find space for us in your hearts among all waves of all the horrific news in the world,” wrote Yassmin Abdel-Magied, a Sudanese diaspora writer, in a viral Twitter thread yesterday. “There is little I can ask of you beyond remembering us, because the conflict has slipped into a realm that feels impossible to influence.”

Dr. Christos Christou, international president of MSF, said yesterday, “Without an immediate, substantial escalation of the humanitarian response, what we are witnessing now will be the beginning of an even larger tragedy yet to unfold—meaning more people will continue to needlessly die.”

“The conflict has slipped into a realm that feels impossible to influence.”

The vast majority of Sudanese are yearning for peace. Yet history tells us that civil wars in Sudan are generally long-lasting and difficult to end. The country’s first post-independence civil war, known as the Anyanya War, lasted 17 years from 1955-1972. The second civil war, which led to South Sudan’s independence, lasted 22 years from 1983 to 2005. The Darfur War lasted 17 years from 2003 to 2020, and the SPLM-North War lasted 12 years (2011-present, albeit with periods of calm).

Depending how one counts, this is the Fifth Sudanese Civil War. How long will Sudan’s long-suffering people have to endure another terrible war? Another generation risks grows up scarred by violence, impoverished, and exiled from home. There needs to be far more urgency to end this conflict—and to mitigate its catastrophic effects—before six months turns into a year, a year turns into five, and six million displaced people turns into eight, ten, or twelve million.