Introductory guide to Sudan's new civil war

Q&A about who is fighting and why

This guide is for readers who are interested to learn more about the war in Sudan but don’t have any knowledge about it. Please consider sharing this article with a friend, colleague, or family member to help us raise awareness about the conflict.

To receive detailed news updates, sign up for our email newsletter:

What’s happening?

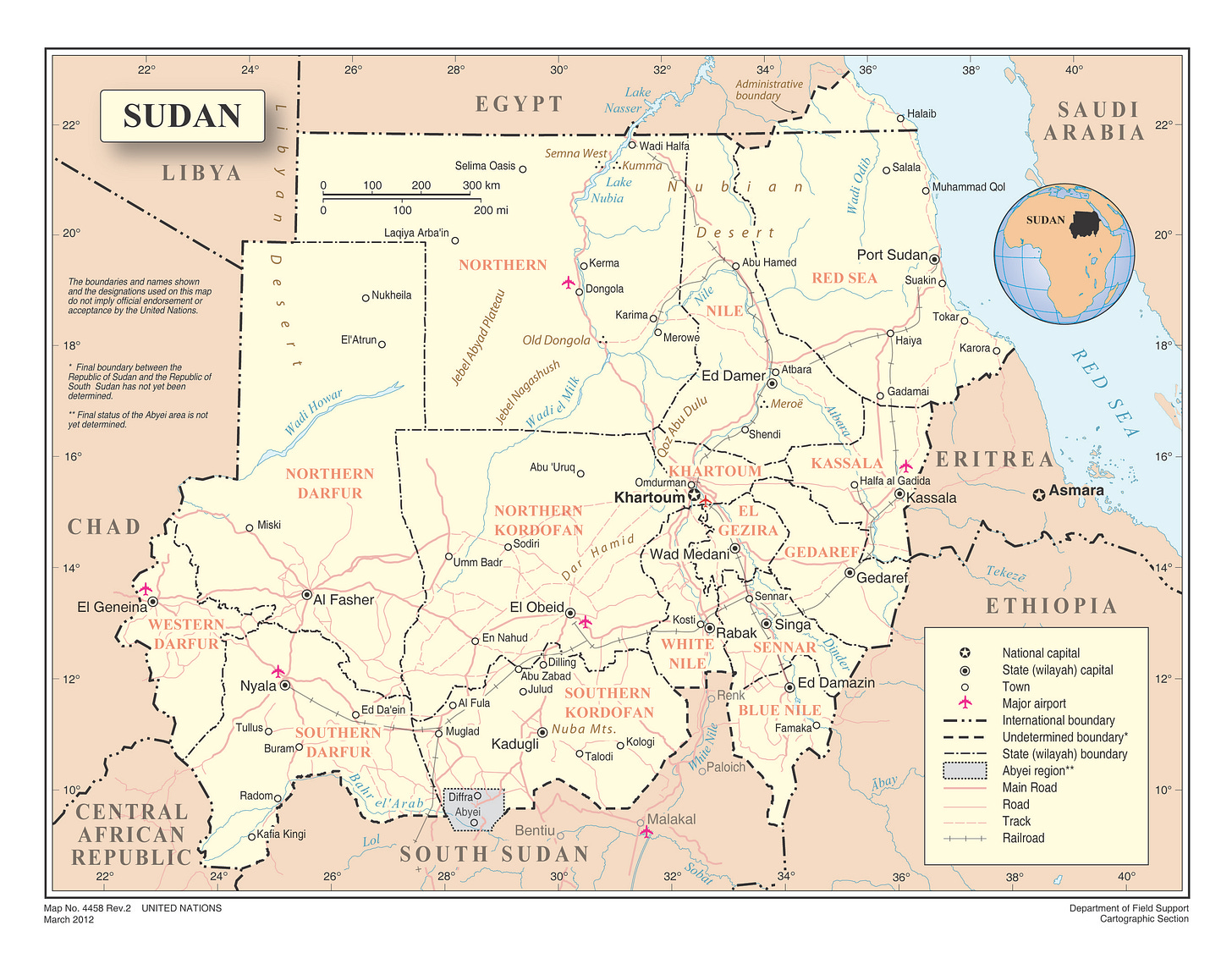

A civil war in Sudan has devastated the nation’s capital Khartoum and several other cities, caused millions of people to flee their homes, and created a deep economic crisis. Sudan’s conflict is now considered the cause of the world’s largest humanitarian disaster. The health system has collapsed in large parts of the country, there are disease outbreaks among the displaced, and there is growing risk of famine.

Who is fighting?

The Sudan Armed Forces (SAF), which includes the army, navy, and air force, are battling the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a regional militia created by the government to help suppress an earlier rebellion in the country’s western Darfur region.

In addition to these two main belligerents, there are some other armed groups in the country that originated in previous wars. Some of these third parties have taken sides in the conflict between SAF and RSF, while others are neutral.

When did the conflict start?

Political tensions between the Sudan Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces began building up in 2022. The two sides also began reinforcing their troops in the capital, resulting in growing distrust between the two sides. On April 15, 2023, fighting erupted suddenly in Khartoum, and spread quickly to other areas. Both sides claim that the other side fired the first shot.

Why are they fighting?

Put simply, the war is a struggle for power. In particular, the RSF leader, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, has shown an interest in acquiring a leadership position, such as president, though he claims not to desire this. His troops acclaim him as “president,” “commander-in-chief,” or “emir,” but he lacks popular support in most of the country.

On the SAF side, the leadership likewise are keen to retain power, and they won’t agree to the RSF’s demands to give up power and to arrest leaders of the former regime, some of whom fled from prison when the conflict erupted in April.

Additionally, the conflict has a significant ethnic dimension. Dagalo is ethnically a Darfur Arab and most of his troops are likewise Darfur Arabs, whereas the leadership of the SAF are mostly Nile Valley Arabs, and the rank-and-file are diverse.

Some of the RSF espouse a racial supremacist ideology that pits them against the non-Arab tribes of Darfur and portrays other Sudanese Arabs as inferior Arabs or not real Arabs. This dynamic has resulted in massacres perpetrated by the RSF and allied local militia in Darfur against the Masalit tribe, echoing the events of the Darfur genocide that took place 20 years ago. Likewise, the SAF have carried out mass arrests and extrajudicial killings on an ethnic basis.

Who is winning the war?

Both sides have claimed to be winning the war. In our assessment, the RSF have gained the upper hand militarily. However, it is unclear if the RSF will be able to achieve a decisive military victory. There is a high risk that the conflict could go on for years if there isn’t a ceasefire and political settlement of some kind.

Currently, the RSF control most of Khartoum and most of western Sudan, while the SAF control most of the north and east. Because the army lost control over most of the capital, Khartoum, they have relocated most government institutions to a new de facto capital, Port Sudan. Some institutions were relocated to Wad Madani, which also became a humanitarian hub, but the RSF captured that city on December 18, dealing a major blow to the army’s morale and prestige.

The above video, filmed from a high-rise during fighting in downtown Khartoum, gives a sense of the devastation in the national capital.

How many people have died?

More than 12,000 people have died in the conflict as of December 1, 2023, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). However, that number is a conservative estimate. It doesn’t include unreported military or civilian deaths, which could be in the thousands. Additionally, ACLED data doesn’t include excess mortality caused by the conflict indirectly, such as deaths caused by malnutrition or disease outbreaks that otherwise would not have occurred.

The true toll is in the tens of thousands.

In addition to these fatalities, thousands of people have been wounded, and at least 5,000 people are detained as prisoners of war or political prisoners.

What kind of government does Sudan have?

Sudan’s federal government is controlled by a military junta, called a “Sovereignty Council.” The country doesn’t officially have a president, prime minister, or parliament. The Sovereignty Council consists mostly of military officers and some former rebel leaders who signed a peace agreement with the government in 2020.

Is this a religious conflict?

No. Most soldiers on both sides of the conflict are Muslims.

However, the ideology of political Islam, as practiced by the former National Islamic Front government of the ousted dictator Omar al-Bashir, plays a role in driving the conflict, according to some analysts. In particular, the religio-political ideology of the former ruling party has influenced many officers of the Sudan Armed Forces.

For its part, the RSF claim to be fighting to rid the country of the “remnants” of this former Islamist regime, though the RSF itself was created to defend the former regime.

This war should not be confused with the previous Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005), which was fought mostly in South Sudan, and which sometimes was framed as a religious conflict, because of the substantial Christian population in South Sudan.

Who are the leaders of the warring parties?

The Rapid Support Forces are led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (nicknamed “Hemedti”) and his brother and deputy, Abdelrahim Dagalo.

The Sudan Armed Forces are led by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and other commanders serving on the Sovereignty Council. For more details about these leaders and the leaders of other armed groups, check out this article:

Has Sudan suffered previous conflicts?

Sudan has a complex history that involves a series of different conflicts, but also periods of relative peace. Depending how one counts, this is Sudan’s fifth civil war since independence in 1956. The previous wars include:

First Sudanese Civil War (Anyanya War): 1955-1972

Second Sudanese Civil War (SPLM War): 1983-2005

Darfur War: 2003-2020

SPLM-North War: 2011-2020

Historians and analysts have identified some common causes and conflict drivers in each these conflicts, as well as key differences. For instance, the first two civil wars involved separatist elements, but the current conflict does not involve any separatists.

The current war is most closely connected to the previous Darfur war. During that war, the Bashir regime armed ethnic Arab militias, colloquially called “Janjaweed” (derived from a word for “demon”), which it eventually institutionalized as the RSF. Now, the RSF have themselves rebelled and, ironically, many of the former rebels are now aligned with the army, though others have stayed neutral.

What about the massive protests in Sudan a few years ago—how is the conflict related to that?

Sudan enjoyed a period of relative peace from 2019-2023, after the Sudanese Revolution. That was a popular uprising that started in December 2018, leading to the toppling of the long-time dictator Omar al-Bashir. Millions of pro-democracy protesters took to the streets, demanding civil rights and a more peaceful future.

After months of mass protests, in April 2019 the military ousted al-Bashir, and partly turned over power to a civilian government, headed by a civilian prime minister. This civilian-led government had plans for elections and security sector reform. They made peace with some Darfur and Blue Nile rebel groups, and they put the former dictator and some of his henchmen on trial.

However, the military never fully relinquished power, and in October 2021 they carried out a counter-revolutionary coup d'état, ousting the civilian component of the government. After that, the army ruled the country in partnership with its paramilitary ally, the RSF, until the two security services turned on each other. Unfortunately, the rivalry and ambitions of these two groups has plunged the country into war, and shattered the hopes of the pro-democracy protesters.

Does this war have anything to do with South Sudan?

No, not really. South Sudan achieved its independence from Sudan in 2011 and fought its own internal civil war from 2013 to 2018. The country still has close economic and social ties with Sudan, so it is impacted by Sudan’s war, but it isn’t directly involved.

Have any foreign governments intervened in the conflict?

This is principally a domestic civil war, and there are no outside powers that have sent troops to Sudan or intervened actively in a major way. However, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) allegedly has sent weapons to the RSF, and provided political support.

Chad allegedly facilitated UAE arms transfers through its territory. The RSF also have business ties with various Russian entities, including the Wagner mercenary group, and a company that supplies drones.

However, there is no evidence of direct Wagner military activity in Sudan.

For its part, the Sudan Armed Forces received limited assistance from Egypt and from Ukraine. SAF also has established relations with China, Iran, and Russia, from which it acquires weapons and materiel. However, these relationships are merely transactional. Diplomatically, both sides are quite isolated, particularly the RSF.

What’s being done to stop this war?

During the first months of the war, the United States and Saudi Arabia jointly brokered several ceasefire agreements, but both sides flagrantly violated these ceasefires. After a pause of several months, negotiations between the warring parties resumed in October, resulting in an agreement on humanitarian access and some confidence-building measures. However, the two sides again failed to comply with this agreement.

Frustrated by the lack of progress in the talks, the United States and the European Union have imposed financial sanctions on leaders on both sides, whom they accuse of fueling the conflict. But these measures have not had any noticeable impact.

The East African bloc IGAD and the African Union have joined the U.S. and Saudi Arabia as joint mediators of the talks. They also held their own summit of East African leaders, which attempted to pressure the two sides to agree to a ceasefire.

Domestically, Sudanese civilian groups have launched a coalition to try to end the war and create a civilian alternative to military rule. Known as Taqaddum, this coalition is headed by former prime minister Abdalla Hamdok. International actors, including IGAD, the US, and the EU, have portrayed this coalition as a potential government-in-waiting, or at least a step toward creating a transitional post-war civilian government.

Sudanese and international groups have also launched numerous humanitarian efforts and advocacy campaigns to respond to the crisis and mitigate its effects. The United Nations and established aid agencies have fed millions of people and provided healthcare. But they lack enough funding to address the crisis comprehensively. Grassroots Sudanese humanitarian groups, known as Emergency Rooms, have also stepped up to meet needs, often working in areas inaccessible to the UN.

Support our journalism

Sudan War Monitor began as a volunteer project after the outbreak of war in April 2023. If you like our work, please consider signing up for a paid subscription so that we can sustain our mission and continuously improve the quality of reporting.